At 74, Feminist Joan Nestle Considers the future.

As a Gen Next lesbian with a master’s in women’s studies and “Feminist” tattooed on my forearm, I wanted to speak to lesbian-feminist elder Joan Nestle about the emerging trends in our queer community. Nestle, who belongs to the pre-Baby Boomer generation often referred to as the Silent Generation, has been anything but silent on issues of queer culture since she was a teenager in the bars of Greenwich Village. Back in New York for the 40th anniversary of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and fresh from editing the “Lesbians and Exile” edition of Sinister Wisdom, she was the perfect person to ask about the recent shifts in LGBT culture.

Do you think lesbian identity is being erased by queer identity, politics and the collapse of gender binaries?

The challenge is: What do these identities mean, and are there bigger things we should be concerned about and joining together about?…What a young woman chooses to call herself from, another era would never alienate me because she has to experience her own history. We have to listen to each other’s histories. As a writer, the last thing you want to do to anyone is shut the door on them explaining themselves. So for me, the word “lesbian” is inclusive of everything—it always has been. It’s inclusive of queer, it’s inclusive of bisexual, it’s inclusive of transgender, and it’s certainly inclusive of feminism. So it becomes the word for all kinds of encounters between all kinds of people who we would call women, or variations of queer. So I just expand “lesbian” to be inclusive of everything everybody seems to be afraid of.

If women don’t want to call themselves “lesbian,” certainly it saddens me, [but] it’s an historical position—it’s their historical position. Somehow, we have to find a way to not turn off from listening to each other [just] because they don’t use the noun that [you want them to]. The wisest thing is to listen and to get to the deeper part of the story. If the woman or the person in question doesn’t want to be called a lesbian, listen to their next sentence. And then to those of us who do call ourselves lesbians, it sort of means that we present our ideas and our feelings and our body in a way that they can find a touch in it, as their voices touch me. There’s a lot of thinking to be done as to what is really being said behind those statements. It’s almost a fear of disappearing, like being butch isn’t good enough. You really just have to be honest to your own politic and your own history and not bully anyone out of or into anything.

Does feminism still have a place in queer politics?

Articulating woman-ness is important, and so is articulating the feminism of queerness. Because queerness without feminism will never carry us through these days. Feminism can’t be erased. It’s like the oxygen we breathe. So, even the women saying “I’m not a feminist”—they’re saying that is a feminist act. They can announce that they have control over their identity. That’s a feminist principle. I think we just have to keep explaining; they can’t take territory from us that we don’t give up, and we must never be ashamed of saying “I’m a feminist.” There were women who tried to run me out of the word “femme.” Life is a chance to discover oneself and one’s connection to others. You lose your life if you run out of fear of what others think they see.

Has there been a resolution in terms of how the community sees your identity?

It still fascinates me because it’s always shifting, but no: There are people who disagree with me, and I just have stood my ground. I am who I am, and I’ve made a life’s work out of it. I’m a ’50s femme. I’m going to tell you a story. Di, who is 12 years younger than me, she was part of a pioneering generation of Australian feminism…I meet her in 1998 and we become lovers. She identifies as a Marxist lesbian-feminist and knows nothing about the butch-femme stuff. I thought, How am I going to make my desires have meaning to her? She’d never used a dildo before; she’d never worn a harness. I come home from teaching and there she is, sitting on the couch, wearing a pajama top, a harness, and a huge dildo, and reading the paper. So we start to make love and I’m on top of her and I look down at her face and she has this huge smile. Now, I’ve been with butch women and what a dildo meant to them was an extension of their bodies. And in the midst of things I was curious what it meant to her, so I said, “Honey, what are you smiling about?” And she said, “I’m so happy to be able to make love to my ’50s femme.” It was such an important moment, because it told me something— that I’m a ’50s femme no matter who I’m with. It’s an act of the imagination to enter into all histories.

Do you think young queer women know who you are—the work you’ve done?

I never take for granted that anyone should read my work or that it has any special truths in it. But when a young woman does read it and says she has found some truth in it—no, no, I would much prefer to listen. I won’t be here to see the fruition of your lives. I want to listen to them. You can’t tell a young person, a person who’s entering history in their own time, who they should be and what they should listen to. I do think intergenerationality is crucial. That is a gift to ourselves.

For you, it’s important that lesbian history is seen as a living thing.

Yes, I was inspired to co-found the Archives by what came out of the generation of women I met in the bars when I was in my teens and they were already in their 40s and 50s, and I saw such incredible undocumented courage. These were taxi drivers, sex workers—all kinds who never get included in history. So the Archives were a site of social history. So it’s an activist site. And we took our banners into the streets. The LHA banner was in the streets for the anti-apartheid movement, Reagan’s invasion of Central America… We never had a constricted view of what the Archives meant—a living, sharing of touch, of the mind, of the body. We had a saying: “Send us something in the language you make love in.”

What do you think of marriage equality being the focus of LGBT rights?

I don’t want to get married. For me, it’s not on the top of my priority list. It’s become the main focus, but what happens to these other things? We’re going to create new exiles. So if you’re a real lesbian, you get married? Then we’ve created our own spinsters. Now I really am a spinster—a lesbian who doesn’t marry! All this normalizing…The real challenge is, how do we give the things that marriage gives to people to anybody? So, immigration rights—why should you have to get married to have them? The issue is, you either join with the haves or you try to start movements, and movements take a long time.

Is ‘queer’ a viable politics? Can it change the system?

Is ‘queer’ a viable politics? Can it change the system?

I love “queer.” I see “queer” as meaning that which deviates from the script. Political resistance is “queer.” You live the best way you can, with the biggest awareness that you can, and try to mitigate suffering, if you can. That’s what it means to be human. There’s no purity to one position.

You’re on Facebook and you blog. Is social media making us compassionate or cruel?

All our creations are of the imagination—they can go in either direction. I have seen the efficacy of organizing demonstrations through social media. But social media is quick and it can lead to hardened positions. It calls for great agility of the mind. As a writer, I resist the short, instant message. I write in paragraphs. I’m sending out memos to the world.

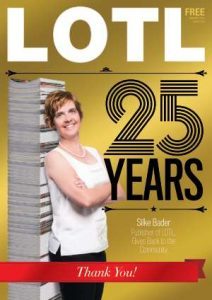

*This article was originally published in the January 2015 issue of LOTL.