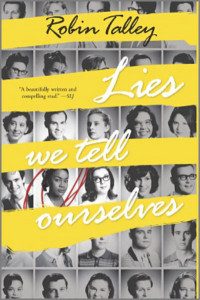

It’s high school during the Civil Rights Movement, can affection transcend complexion for a black girl and a white girl?

It’s high school during the Civil Rights Movement, can affection transcend complexion for a black girl and a white girl?

It’s 1959 and Virginia is for haters.

So it’s understandable that Sarah Dunbar, a black teenager selected to transfer from one monochromatic institution to another, hardly sees herself as the great white hope of integration.

Horrified that once their school goes black it’ll never go back, the uncivil whites refuse to turn a colourblind eye to Sarah’s presence.

One such prejudiced pupil is Linda Hairston, who’s been brought up to bring up her racial superiority every chance she gets. Talk about playing the race card.

When the girls’ French teacher instructs them to collaborate on a class project, neither is tickled pink. They get on each other’s nerves, into each other’s heads, and under each other’s skin.

Sarah begins to believe that Linda’s pigheaded ideas about pigment are only skin-deep, and Linda starts to realize that right and wrong are not always black and white.

Soon, affection transcends complexion. Linda might never utter the prescient proclamation “I have a dream,” but for now, she can not-so-safely say “I have a dream girl.” Sarah, similarly, will be young, gifted, and blacklisted if her family finds out.

When their secret comes to light, will either girl do the right thing or the white thing and save her own skin?

Robin Talley’s debut novel is a textured, sincere, and unstinting story of first love. It is told from both protagonists’ points of view, underscoring the imperatives of equity and equality.

Talley tells me: “Sarah’s head was much easier to get into than Linda’s. It’s true that Sarah’s African-American and I’m not. The thing is, though, Sarah, unlike Linda, is right, which made her perspective much easier to wrap my brain around. The things Linda believes ― and, at the start of the story, she believes them with all her heart ― are so wrong, so repugnant, that it was really, really, really hard to try to write from her perspective. It was a huge amount of intellectual work, trying to wrap my brain around her belief system and then describe it so that readers would understand her thinking. Writing from Linda’s point of view is the greatest challenge I’ve had yet in my career.”

It’s a challenge Talley rises to and overcomes. The writing is searing, the characters endearing, and the themes of bigotry and parity ridiculously relevant.

This book will make you think without thinking about it. As you take it all in, you might take offence. You might also take action. You might even take a chance. But you won’t take it back.

So you can tell yourself you won’t like Lies We Tell Ourselves, although don’t we tell ourselves enough lies already?