The book that made me a lesbian.

I don’t have it anymore, that novel I stole when I was a freshman in high school. It and about a half dozen others I took were on a shelf hidden behind a sofa at one of the homes where I babysat regularly.

I hated babysitting there–I didn’t like the child and the single father with whom she lived was very handsy. But the night I found those books–I’d had to move the sofa to retrieve a toy–it was like that door in the “The Secret Garden.” It was an entrée into a world I didn’t know existed, but of which I yearned to be a part.

That night, after the child was in bed asleep, I moved the sofa again and pulled out the books. The entire bottom shelf was nothing but lesbian pulp fiction–about 30 books, maybe more. The covers were sexy and what my mother would have called “lurid.

I felt a frisson of something as I looked at them–I knew this was forbidden fruit. That the books had been hidden away only underscored that fact. But as I had learned about Eve as a Catholic schoolgirl, forbidden fruit inevitably got eaten.

I was about to commit two sins–stealing and reading books that I just knew were on the condemned list. Did I feel guilty? Not really. I just didn’t want to get caught.

I sat cross-legged on the floor, all the books spread out in front of me. I was an avid reader and it had always been difficult to choose the ten books I could take out of the library at once. But this dilemma was different: I was going to steal these books. I had no intention of ever returning them. I wanted all of them, but even if I had had a place to put them all, I knew they would be missed.

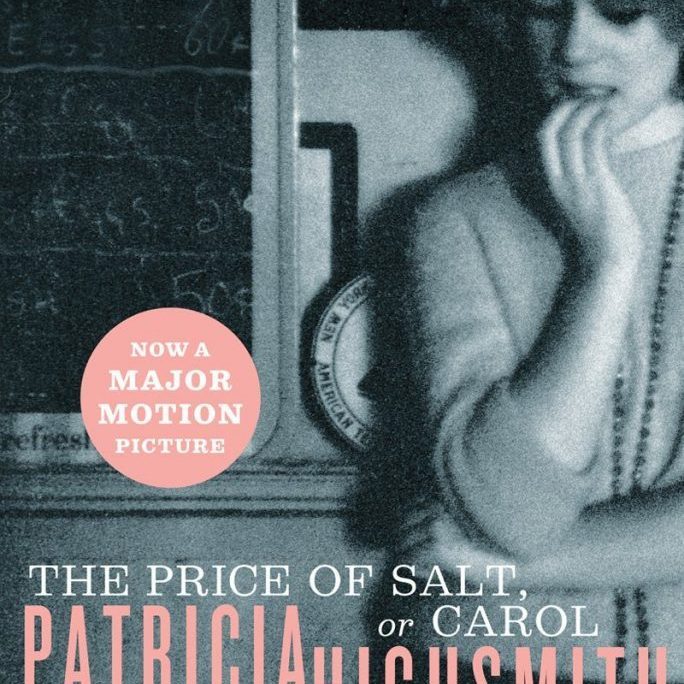

I read the back covers of each. I skimmed a few pages of each. And then I made my choices, carefully fitting the books I was taking into my backpack. There were Beebo Brinker novels, like “Odd Girl Out” by Ann Bannon and books by Ann Aldrich and Vin Packer. Years later I would learn those two writers were actually the same person, Marijane Meaker. There was a book by Artemis Smith called “The Third Sex.” And there was a book by Claire Morgan–”The Price of Salt.”

“The Price of Salt,” also released under the title “Carol,” was the book that changed my life. There was no Claire Morgan. The novel was actually written by Patricia Highsmith, a world-renowned mystery novelist. The novel she had written prior to “The Price of Salt” was “Strangers on a Train,” which had become a Hitchcock thriller the year before.

If there was a moment when I knew for certain I was a lesbian, it was when I skimmed the first pages of Highsmith’s novel. I could imagine myself in the words that I read, the lesbian words, the lesbian images. All the words Highsmith wrote that I had never seen put together exactly like this before because I had been a Catholic schoolgirl and we didn’t talk about other girls, we only talked about boys, but there was always something not-quite-right about that for me.

And then there was “The Price of Salt” and sitting cross-legged on the carpet I read,

“Their eyes met at the same instant moment, Therese glancing up from a box she was opening, and the woman just turning her head so she looked directly at Therese. She was tall and fair, her long figure graceful in the loose fur coat that she held open with a hand on her waist, her eyes were grey, colorless, yet dominant as light or fire, and, caught by them, Therese could not look away. She heard the customer in front of her repeat a question, and Therese stood there, mute. The woman was looking at Therese, too, with a preoccupied expression, as if half her mind were on whatever is was she meant to buy here, and though there were a number of salesgirls between them, Therese felt sure the woman would come to her. Then, then Therese saw her walk slowly towards the counter, heard her heart stumble to catch up with the moment it had let pass, and felt her face grow hot as the woman came nearer and nearer.”

What was it about “The Price of Salt” that affected me so much? I think it was the accessibility of it. Unlike the other books I stole that night and the other women on those pages, Carol and Therese seemed like people I might know. They were calm and rational and real and I could see them so clearly in my mind’s eye and I knew I would know them one day.

Or be them.

I could see myself being Therese in just a year or two and in fact, I had a job after school in a department store at Christmas the year after I first read “The Price of Salt.” I kept imagining Carol–or a woman like her–would come into the department store looking for the perfect Christmas present which I would somehow be able to find and we would have the same conversations about reading that Carol and Therese have and she would leave her gloves at the counter as Carol does and I would have to search for her and then we would fall in love.

I wished as hard for that at Christmas as for anything that year.

When Therese goes home after meeting Carol, it’s all she can think about–their meeting. Because the thing that Highsmith’s novel explains to us without explaining at all is that lesbians know each other, that lesbian desire and those filaments that charge within us when we meet is there, it’s inside us, just waiting to be switched on.

“But there was not a moment when she did not see Carol in her mind, and all she saw, she seemed to see through Carol. That evening, the dark flat streets of New York, the tomorrow of work, the milk bottle dropped and broken in her sink, became unimportant.

She flung herself on her bed and drew a line with a pencil on a piece of paper. And another line, carefully, and another. A world was born around her, like a bright forest with a million shimmering leaves.”

While other girls my age were imagining being swept off their feet by some ultra-cool countercultural rock star, I was dreaming of a suburban housewife driving into the city to go to the best department store–the one in which I worked.

I was dreaming of the woman who would sweep me off my feet, the older, beautiful, interior, intellectual woman who would bring me back to her world of books and words and lesbianism and teach me the things I had yet to know.

Todd Haynes’ film of Highsmith’s iconic novel, “Carol” opened in limited release in the U.S. on November 20 and will open in the U.K. on Nov. 27. The film debuted as part of the film festival circuit in Philadelphia in October at the Philadelphia International Film Festival.

Cate Blanchett is the perfect evocation of Carol. Cool, serene, guarded, yet immensely confident. This is a woman who knows exactly who she is and what she wants and when she meets Therese (Rooney Mara), the vivid drama of Highsmith’s dark romance enfolds us, just as the book enfolded me as a teenager. Blanchett’s Carol takes us the same way she takes Therese, the same way Highsmith took thousands of young lesbians, sweeping them up into Carol’s arms with words by turns artful and raw.

“Then Carol slipped her arm under her neck, and all the length of their bodies touched fitting as if something had prearranged it. Happiness was like a green vine spreading through her, stretching fine tendrils, bearing flowers through her flesh. She had a vision of a pale white flower, shimmering as if seen in the darkness, or through the water. Why did people talk of heaven, she wondered.”

“The Price of Salt” was published in 1952. Before I was born before you were born. Highsmith was born the same year as my paternal grandmother. And yet for me, reading the novel 20 years after it was published, Highsmith had reached me as if she were my contemporary and the scenes I was reading didn’t feel dated, they felt so present, so right now, so much a part of my life as it had likely felt to young women of my own mother’s generation.

Highsmith said she wrote the draft of the novel in one night when she was fevered from chickenpox and after she saw a blonde woman in a hat and fur coat at a department store. In an interview, Highsmith said she “drew on the experiences of her former lover, Virginia Kent Catherwood, a Philadelphia socialite who had lost custody of her child in divorce proceedings involving taped hotel room conversations and lesbianism.”

It’s telling that the paperback of “The Price of Salt,” about “a love society forbids” sold over a million copies. In the 1950s. There were so many of us already.

Had the wife of the man for whom I babysat been one of them–one of us? Did he have these books because of her? When I babysat for him there were no single fathers. Men didn’t get custody of children. Had he taken his wife’s child because she was a lesbian?

Highsmith has been re-made on the screen many times. The Ripley books. “Strangers on a Train.” But “Carol” has visual beauty and interior depth that hasn’t been seen in a film version of a Highsmith film since Wim Wenders’ gorgeous 1977 film “The American Friend,” an adaptation of “Ripley’s Game.”

Haynes has done with “Carol” what Highsmith did with “The Price of Salt.” He has captured that moment–that moment I had as a teenager sitting cross-legged on the floor in that living room and feeling as if I had just found the key to my own life.

“The Price of Salt” is a very interior novel. There is action, but much of it takes place off the page, of necessity, to keep the story centred on Carol and Therese. Haynes has managed to translate all that interiority to the screen seamlessly, pulling us into the lives of Carol and Therese.

The film has all the rich, super-saturated colour of Haynes’ award-winning 2002 film “Far from Heaven” and he keys into the suspense and tension both women feel in different ways–Carol because she is extricating herself from her marriage and fears losing her child, Therese because she didn’t really know who and what she was before Carol.

Highsmith was 30 when she wrote “The Price of Salt.” It’s different from her other books. The malevolence is “out there”–it’s the spectre of homophobia, which threatens to infect both women and of course, Carol’s child.

But it’s not the murderous malevolence of Highsmith’s other work. This may be why it is so interior. It’s a fragment of Highsmith’s own life–a life in which she, like Carol, like Therese, must remain closeted because no room has been made yet for openly lesbian or gay writers and books that feature lesbian or gay characters who don’t end up in prison or dead, like Martha in Lillian Hellman’s “The Children’s Hour” or Jill Banford in D.H. Lawrence’s “The Fox,” both of which had been made into films a few years before Stonewall.

“How was it possible to be afraid and in love? The two things did not go together. How was it possible to be afraid, when the two of them grew stronger together every day?”

It could. It has that power. It could hold you there in the front row of the darkened movie theatre as Carol holds Therese. But the book must be read, too, because Highsmith’s words are so very compelling.

“An inarticulate anxiety, a desire to know, know anything, for certain, had jammed itself in her throat so for a moment she felt she could hardly breathe. Do you think, do you think, it began.

Do you think both of us will die violently someday, be suddenly shut off? But even that question wasn’t definite enough. Perhaps it was a statement after all: I don’t want to die yet without knowing you. Do you feel the same way, Carol? She could have uttered the last question, but she could not have said all that went before it.”

“The Price of Salt” was magic for me. I have never forgotten that particular magic. I have never forgotten becoming a lesbian, for sure, for real, for always, as I read Highsmith’s words, as I met Therese and Carol, as I knew there were real women who were lesbians who I would meet and who I would love and who would define my life as I would define theirs.

The first was Carol.

“It would be Carol, in a thousand cities, a thousand houses, in foreign lands where they would go together, in heaven and in hell.”