What makes real lesbian writing?

What makes real lesbian writing?

It’s a question being asked and argued when Sappho was a girl. And it still keeps coming around, like leaf-peepers in the Fall, and almost as annoying.

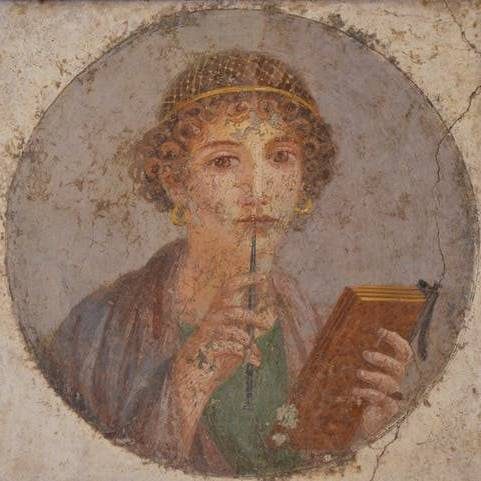

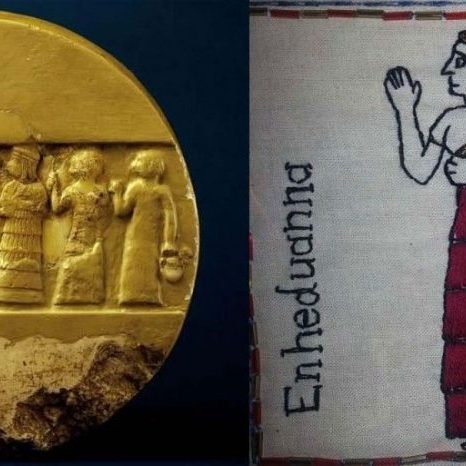

Sappho (610-570 BC) knew about real lesbians – women who watched and waited, were consumed by love and jealousy in a man’s world – or at least, that’s how this could be interpreted…

He’s equal with the Gods, that man

Who sits across from you,

Face to face, close enough to sip

Your voice’s sweetness,

And what excites my mind,

Your laughter glittering. So,

When I see you, for a moment,

My voice goes,

My tongue freezes. Fire,

Delicate fire, in the flesh.

Blind, stunned, the sound

Of thunder, in my ears.

Shivering with sweat, cold

Tremors over the skin,

I turn the colour of dead grass,

And I’m an inch from dying.

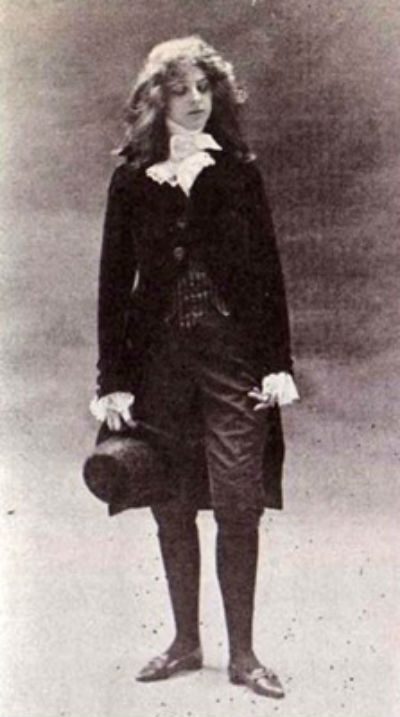

Much influenced by Sappho, Renée Vivien – born plain Pauline Mary Tarn in 1877 in London – also knew about jealousy.

It was part of her long and tempestuous affair with heiress and writer Natalie Barney in whose Belle Epoque salon she flourished and flirted.

In “The Touch”, Vivien wrote:

The trees have kept some lingering sun in their branches,

Veiled like a woman, evoking another time,

The twilight passes, weeping.

My fingers climb,

Trembling, provocative, the line of your haunches.

My ingenious fingers wait when they have found

The petal flesh beneath the robe they part.

How curious, complex, the touch, this subtle art –

As the dream of fragrance, the miracle of sound.

I follow the graceful contours of your hips slowly,

The curves of your shoulders, your neck, your unappeased breasts.

In your white voluptuousness, my desire rests,

Swooning, refusing itself the kisses of your lips.

Vivien wrote in French, so it’s possible that “the line of your haunches” would sound sexier if “les cuissots” were substituted for what otherwise sounds like a Sunday roast. Nevertheless, the study of the many images of Barney suggests she was the subject of Vivien’s passionate verse.

As one of the more infamous Parisians of the time, Natalie Barney was as real a lesbian as ever-inspired women, including Radclyffe Hall. As salon hostess Valerie Seymour, a character in The Well of Loneliness, Barney unwittingly lends the most miserable book of the 20th century one of its more positive images: “Valérie, placid and self-assured, created an atmosphere of courage….”

Most enduring, however, was Barney’s 50-year relationship with American heiress and painter Romaine Brooks nee Goddard – yes, she married, albeit disastrously. Unlike many of their contemporaries, the two lived into old age: Natalie in Paris, Romaine in Nice.

“We do not touch life except with our hearts,” Natalie poignantly wrote. But ironically, among these self-consciously literary women of letters, the last word belongs to Romaine Brooks, whose body of work – obscure during her lifetime – is now in many distinguished museums. She devised her own epitaph, and it’s as wryly poetic as anything by the “real” writers:

“Here remains Romaine, who Romaine remains.”