There is a moment in Hannah Gadsby’s Ten Steps To Nanette that spoke so eloquently about an experience I have never quite been able to articulate that I had to put the book down and make a cup of tea.

Recalling her upbraiding by an art teacher following her submission of a fact-filled essay, Gadsby writes:

I felt ashamed that I hadn’t understood what had been expected of me, and even more ashamed by the fact that art on its own apparently didn’t make me ‘feel’ anything. I understood that art made other people feel things, and I thought that if I could understand what it was that made the feeling happen then I would be able to have the feelings too.

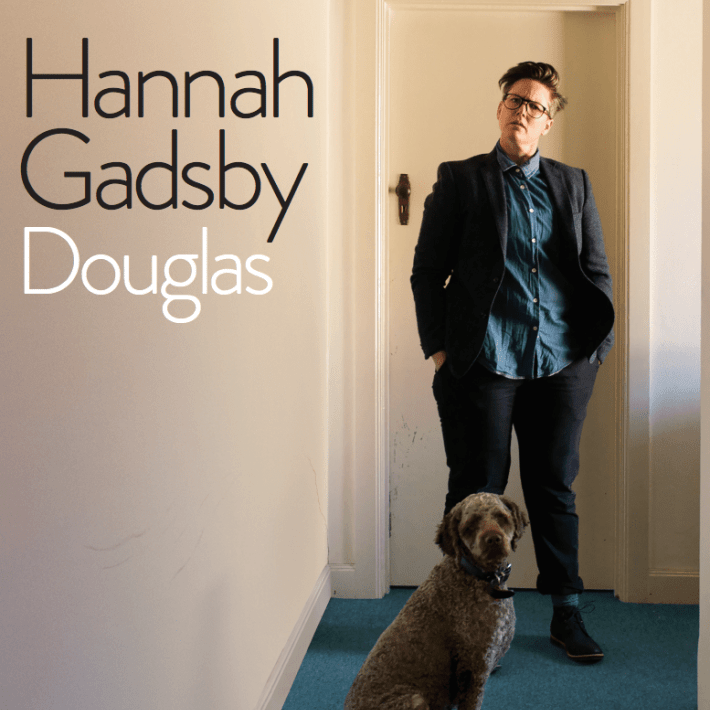

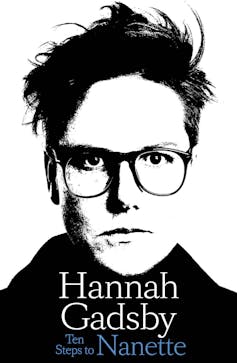

Review: Ten Steps to Nanette – Hannah Gadsby (Allen & Unwin)

Like Gadsby, it was not until my adulthood diagnosis of autism that I had the gift of self-knowledge that comes with understanding how your brain works. Reading Gadsby’s reflection on that essay, I wanted to read it myself: it seemed such a clear example of something autistic author Steacy Easton has described in an essay for Kadar Koli as the way “exchanging facts, exchanging the taxonomic list, becomes an act of solidarity and intimacy” for autistic people.

In writing Ten Steps to Nanette and offering her obsessions such as art history (which she studied at university and has presented gallery tours, stand-up and TV shows about), narrative structure and the creative process, Gadsby has shared her taxonomic list.

Comedy success and life as a genderqueer autistic person

Readers who come to this memoir to discover how Gadsby created her successful show will not be disappointed; nor will readers interested to hear how she rose through the comedy ranks. She writes about both things with engaging candour, particularly about how Nanette gaining traction during the #metoo era has “been recontextualised as merely my response to [#metoo], and not as something I created under a completely separate set of very personal compulsions”.

Turning narrative expectations on their heads, Gadsby begins the book with “Step One: Epilogue”, which serves as a flash forward – a short glimpse into her post-Nanette life as the toast of Los Angeles industry parties. There may be readers hungry for more Hollywood gossip. Still, those opening pages are the last we hear of her more recent successes before Gadsby plunges us back in time and guides us, more or less chronologically, through her life as “a financially insecure autistic Australian gender queer vagina-wielding situation”.

Gadsby’s family are presented with an incredible warmth that never drifts into cheap sentiment. We are delighted by her mother’s outrageous knack for a gag at her own (and often others’) expense – an early stand-up gig where her mum heckling eventually provides a nervous Gadsby with her punchline is hysterical – even as we sometimes recoil from the same woman’s complex journey towards accepting Gadsby for who she truly is.

Gadsby’s eye for character detail is sublime. In one moment, where her teenage self rides a tortuous route home to avoid being teased for her polystyrene helmet by local cool kids, she arrives home hours late, anticipating her mother’s wrath: “I found her out by the washing line being angry at the pegs.”

Similarly, Gadsby offers a complex and nuanced account of life in small-town Tasmania in the 1980s and 90s, with heartfelt portraits of people who mattered to her (and even some who didn’t) alongside the simple fact of it being an environment where class divides were deep, and racism and homophobia were rampant. This is not a memoir of the good old days – rather, a stark reminder of what those days did too good people.

With an adult’s wisdom, she reflects on her early childhood memories of the woman her mother paid to help look after little Hannah. In a short paragraph, Gadsby gives a heartbreaking glimpse into the agony experienced by this “kind and gentle” woman, a survivor of appalling abuse, in her short life. The dignity Gadsby affords people who have slipped through society’s cracks is profound.

If Gadsby is kind to the people who mattered in her life, she also treats her younger selves with dignity and care; she often hypothesises what she might do now if she could travel through time and sit with herself in moments of pain.

Through the book, Gadsby also offers retrospective asides that provide the context she was only able to understand with the hard-won self-knowledge of diagnosis: that, for example, young girls on the autism spectrum are uniquely at risk from sexual predators or that ADHD and autism can affect a person’s executive function (the mental skills used to manage daily life).

Autism is‘ core’ to identity but not defining.

This is not a book “about” Gadsby’s late diagnosis of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, and as she is quick to note in “Step Six: Whirl, Interrupted”,: “my neurobiology is at the very core of my thinking and, as such, it sits at the heart of who I am – but it does not define me”.

She carefully discusses the barriers to diagnosis faced by older women and gender-diverse people, whose experience may not fit the male-skewed diagnostic criteria and the fact that diagnosis is expensive and difficult to obtain. She also knows that discussing one’s diagnoses invites “the howling opinionated rage of others”. But there is a specificity to Gadsby’s prose that, like Emma A. Jane’s recently published and equally bracing memoir Diagnosis Normal (Penguin), makes Ten Steps a thrillingly and distinctly autistic read.

Gadsby writes that she does not “have the luxury to skip over” the myriad myths surrounding ADHD and autism. I am about to introduce one here to pinpoint a quality of Gadsby’s work that I suspect will be dismissed rather than celebrated. (I don’t need to suspect, in fact; one US review bemoans Ten Steps’ “exhaustive and, at times, a tad exhausting” recollection of Gadsby’s youth.) The notion that autistic people are best qualified to tell autistic stories is still nascent; to write about autistic literature, even as an autistic person, still necessitates the act of filtering through what has come before.

Creative echolalia and language as survival

One of Ten Steps’ most striking qualities is Gadsby’s use of repetition and echo; what might be described, were she to read the book aloud, as scripting or delayed echolalia.

Delayed echolalia constitutes the “reciting” of words and phrases the autistic individual has heard after the fact (typically, these “lines” are lifted from favourite TV shows and movies, and so on). Immediate echolalia is something repeated as soon as the autistic individual hears it. (A parent asks, “Do you want some juice?” and the autistic child responds, “Do you want some juice?”.) Immediate and delayed echolalia is one of several repetitive behaviours that form the basis of the clinical model of autism and are often dismissed as devoid of meaning or context.

In Gadsby’s skilled hands, however, we see the true creativity, meaning and shifting context of echolalia in all its beauty. Nowhere is this more evident than in the chapter “Step 3: The Formative Years”, which begins with an overview of Tasmanian history subtitled “STOP! CONTEXT TIME!”, a riff on MC Hammer’s U Can’t Touch This.

Throughout the chapter, Gadsby continues to riff on the song’s refrain as she braids a clear-eyed account of the movement towards the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the state, and its attendant public expressions of courageous queer rights activism and virulent homophobia, with her own experience as a then-closeted adolescent.

Step 3 is the book’s devastating tour de force, its events concluding one year after the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Tasmania with the experience Gadsby also described in Nannette: when a local young man bashes her for being “a lady faggot”.

At the outset of the chapter, Gadsby introduces her childhood fascination with jingles and ads and her habit of “quoting ads out of context […] to make people laugh and avoid answering difficult questions simultaneously”. One go-to riposte was lifted from the Colgate Fluorigard ad campaign: “The same way liquid gets into this chalk.”

The Fluorigard line and MC Hammer riffs repeat throughout the chapter, each time gaining narrative heft. At this, I thought of M. Remi Yergeau’s Authoring Autism, in which they write (of scripting and echolalia) how “each echo can constitute its discursive unit […] it can also serve as a placeholder for multiple meanings”.

Each time Gadsby repeats the Fluorigard line, its meaning shifts. The MC Hammer riff, which initially reads as a mood-lightener, soon becomes unrelenting. By the time “STOP! GOOD NEWS TIME!” is deployed, the reader may be surprised to discover that the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Tasmania did not magically expunge the Apple Isle of the violence of homophobia. It’s a remarkable rhetorical sleight of hand, but it does not exist simply to be clever: it shows the reader how Gadsby used (and uses) language and writing to navigate and survive an often cruel world.

No ‘straight line’ through trauma

It may be tempting to frame Ten Steps as another example, as Gadsby notes in the “Intermission” that follows Step 3, the world’s hunger for “gratuitous details in exchange for empathy”. As Gadsby reminds the reader at several instances in Ten Steps, “there is no such thing as a straight line through trauma”, but in the autistic quality of the book’s writing, these echoes and repetitions guide the reader through trauma’s mirror maze, taking us inside Gadsby’s experience of her world.

The book’s keen focus on sensory detail – the slipperiness of someone’s awful satin sheets; the blissful relief of a temperature-controlled gallery when compared to a musty, hot school library; the sweaty smell of little lunch sandwiches encased in plastic; the sound of a horrible hipster cafe – has a similar effect. In inviting the reader into this deeply felt, sensorially-focused world, Gadsby gives them the gift of empathy.

If Ten Steps To Nannette were solely an account of the writing of Gadsby’s show, or a memoir, it would be a compelling work. Combining the two, the book becomes the show’s equal that bears its name.![]()

Clem Bastow, PhD candidate, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.