The story of one woman’s Russian adventure.

Borders are psychological and ideological as much as they are physical. Travel teaches us this, which is perhaps one of the reasons I love to wander.

It is through geographical transit that I get to transgress the limits I have placed on myself or the way I preconceive the world. Travel is the best way to truly experience the humanity of others, who are quite literally often portrayed to us as “the other.”

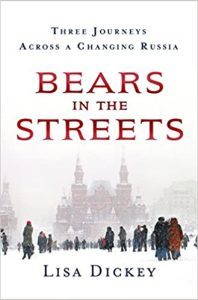

Such is the message of Lisa Dickey’s excellent book, Bears In the Streets, which is a different kind of travelogue, and takes its name from an odd perception Russians have of what Americans think of Russia: that it’s a kind of lawless frontier.

This memoir is the product of three major visits over two decades to a vast and often misunderstood country. Dickey, an out lesbian writer who is based in Los Angeles, undertook lengthy journeys that essentially spanned the breadth of the landmass: in 1995, 2005, and 2015.

During those visits, she struck up friendships with complete strangers—a rabbi and a rap star; farmers, scientists, and lighthouse keepers—who she drops in on again a decade later each time. The effect is rather like Russian nesting dolls or matryoshka. It’s a treat to get to the next stage and compare with what has come before.

Bears In the Streets is an accessible and enjoyable read, and especially relevant in a time when Russia is in the news—Vladimir Putin and the alleged ordinance of internet hacking that possibly affected the outcome of the US presidential election. “The timing is extraordinary,” agrees Dickey.

A self-confessed Russophile, Dickey first became hooked on the land of Stanislavsky, balalaikas, and the hammer and sickle when she was 9 years old. The year was 1976 and her mother took a solo trip to Russia. “I was completely baffled at how she could possibly go and have a vacation in Russia when my father was a U.S. Navy pilot and I knew that part of his job was to fight the Russians,” Dickey tells me. “Russia was our enemy.

And yet my mother could go on a tour there. I just couldn’t figure it out and that planted a seed in my head.” So she studied Russia in college and fell in love with the language and the literature. After college, she took a job as a nanny for a US diplomatic family in Moscow.

And so began a journey in which Dickey traversed thousands and thousands of miles, drank a lot of vodkas, and puzzled over who is free and who is oppressed: Russia or America?

“Even now, yes we are at odds with Russia. Our government is obviously unhappy about the election hacking and meddling that’s been going on but at the same time it would be a mistake to imagine that Russian people are bad people or that we have a quarrel personally with them because I don’t think that’s the case,” says Dickey.

“As I travelled across Russia so many people said, ‘We don’t like your government or what your government is doing,’ and they particularly did not like Barack Obama. But over and over again people would say to me, ‘But we’re really glad you’re here and we’re happy to be having this connection with you.’ ” I caught up with Dickey to probe a little further the timeliness of her book.

Why is the anti-Russian sentiment at an all-time high? Is it just the product of the Obama administration?

If you think about how Russians are portrayed in entertainment—for years, during the Cold War the Russians were the bad guys; they were the bad guys in James Bond movies and the Rocky movies, and then that became less of a thing after the fall of the Soviet Union… But American people don’t really know what Russian people are like.

Having spent a lot of time among Russians, and having experienced the high level of generosity from them, I think it’s a concept we don’t really get. Putin is Putin and the Russians are the Russians. Putin doesn’t equal Russia, in other words, in the same way, that Donald Trump doesn’t equal Americans.

For the sake of argument: What is wrong with having Russia as an ally? The Right seems to now be embracing this as a concept and a geopolitical possibility, but why could we not before?

It is absolutely fascinating to see how it has changed. In the 1980s it was the conservatives and the Republicans who were always saying, “Look out for Russia. We have to be wary of them and they’re the enemy.”

The fact that now we have the Republicans essentially saying “Russia’s fine, let’s just turn the other cheek, this is all good, we want closer relations”—it goes to show that when battle lines are drawn politically between the parties they definitely shift.

The Republican party was the party of Lincoln and that has changed over time to where they’re not the progressive party in terms of race relations. Nothing is ever set in stone and they change depending upon who is in power and depending upon how they can help themselves stay in power.

Putin’s “anti-homosexual” law is misnamed by us in a sense because it’s not really that. Can you clarify?

The law does not outlaw homosexual behaviour. The law outlaws propagandizing homosexual behaviour, specifically to minors.

You’re a lesbian, were you ever nervous or concerned about your freedom while travelling through Russia?

I was very nervous about travelling as an openly gay person, and the first two trips, in 1995 and in 2005 I did not tell many people at all that I was gay. This time around, in 2015, I was married and that made a difference to me.

I didn’t want to lie about that if I was asked and I knew that I’d be asked. And the funny thing about Russian is that you can’t really say “I am married” as a gender-neutral construct, which is how we say it in English. It’s not like I could say, “I’m married but I don’t really want to talk about it.”

You have to either say “I’m wifed” or “I’m husbanded.” There is really no way to answer that question honestly and remain closeted. And so I was very nervous about that, about how I would be received. You never know what might happen; if somebody makes a complaint.

But my experience I have to say was very—I didn’t have any trouble. Almost everybody said, “I’m fine with it, but don’t tell anybody else.” Because their perception was it’s all good but you could run into trouble.

There’s a great quote from a Russian friend of mine who lives in Los Angeles: “The thing about Russia is, everything’s okay until it’s not okay.” If you are planning to go over there and be out and proud, I think that you’d have to be very careful.

In fact, one of the gay male locals you meet and become friends with—Grisha—is murdered. Do you know for sure what happened?

I don’t think we will ever really know. All I know is what his friends told me later, which was that it appeared they had been hanging out, having a fun time, there was a couple of guys and Grisha, and at some point in the evening one of them ended up stabbing him.

It wasn’t really clear if it was a robbery gone wrong or if it was an anti-gay thing. The guy did get caught and he did go to prison. But it’s not a thing that I’m comfortable speculating on.

When Russia hosted the Olympics at Sochi and there were calls for a boycott, what was your view of that?

I totally understood people wanting to boycott, and there was a part of me wanting to take part in that too. I totally support people who are actively protesting what they think are unfair laws…but it really bummed me out that in the 1990s Russia passed a law decriminalizing homosexuality and then nearly 20 years later they pass a law criminalizing or “propagandizing” it.

I wish that the 2013 law had never been passed. I think it was very brave of people to go over there and say, “I don’t support this.”

With such a law, though, Putin was able to grandstand and build a support base for himself, and you can see it happening here with our own president. Maybe we have a date with fate in Russia.

Yes, maybe we do.

Do you think you’ll go back to Russia in 2025?

I’d love to go do this trip again. I feel like these people are my friends. I’ve been dropping in on them for a long time. No matter what our differences of opinion or geopolitical issues, or the leadership of our respective countries, I’ve been treated incredibly kindly by them and do have a connection with them so yes, I’d absolutely love to go back in 2025.

Might Russia ever be a true democracy, perhaps post-Putin?

That is a really interesting question. It’s hard to answer because you invariably lapse into generalizations about the national character. I don’t know that it will happen any time soon. I think that Russians are very happy with Putin for the most part.

The polls show an amazing level of support for Putin. People really seem to love him and to a certain extent, I’m not sure that the freedom you describe is a priority for them as much as it is a priority to have somebody in charge who they feel is in control.

Someone who is making their lives better. There have only been three leaders since the collapse of the Soviet Union and in the people’s experience, Putin stabilized everything—and people’s lives have been for the most part better 2005 to 2015 than they were in the ’90s. This is what they go on.

And what about lesbian culture. There’s a sense lesbians can’t get on with their lives, for example, gay Russian women who want to start a family?

I think for gay couples it would be exceedingly difficult to have a family. How do you do that when there is a law against providing homosexual propaganda to minors and you’re two gay parents? I don’t even know how you would do it.

And without community support.

And without community support.

Absolutely. The gay people that I have spoken with feel like as long as they stay under the radar no one messes with them, and they are content. I don’t think they’d get any support practically. It’s potentially a Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell situation. They tend to be dismissive of this notion of being out or offering a [Pride] parade.

To openly declare yourself is not a part of the Russian psyche?

I think there is a long history of not putting your business out into the world. The walls have ears — particularly in the Soviet era. You just don’t want to tell everybody your business, there’s no benefit to it. Bad things might happen.

What is your wish for this book?

I hope that people can read it with an open mind about who these people really are and gain some sort of understanding. I think our notion of Russia is essentially a caricature: it’s a former evil empire; it’s Vladimir Putin; it’s a lot of hackers; it’s very dark and shadowy.

I hope that people can read this book and see that Russia is not a bunch of evil people who wish us all ill. There are a lot of really good people there, and it’s a fascinating place with a really long history. The book is about the notion of people communicating with people—not just the governments going at each other.

Russia is not just Vladimir Putin the same way that the United States is not just Barack Obama or Donald Trump.