Headcase is a groundbreaking collection of personal reflections and artistic representations illustrating the intersection of mental wellness, mental illness, and LGBTQ identity and the lasting impact of historical views equating queer and trans identity with mental illness.

Headcase is a groundbreaking collection of personal reflections and artistic representations illustrating the intersection of mental wellness, mental illness, and LGBTQ identity and the lasting impact of historical views equating queer and trans identity with mental illness.

The featured pieces offer personal views from both providers and clients, often one and the same, about their experiences. In the anthology, readers will access the inner thoughts of contributors who collectively document the difficulty of navigating flawed healthcare systems that limit affordable access to genuinely affirming, effective services.

Traversing boundaries of race and ethnic identity, age, gender identity, and socioeconomic status, Headcase appeals to LGBTQ communities and, specifically, LGBTQ mental health consumers and their friends, families, and comrades.

We are the experts in our own illness, wellness, and care.”

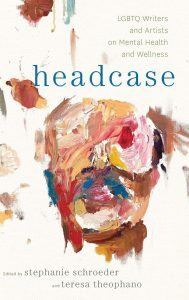

That statement sums up the theme behind Stephanie Schroeder’s brilliant new anthology, Headcase: LGBTQ Writers and Artists on Mental Health and Wellness (Oxford University Press).

The book combines first-person accounts from LGBTQ people with historical and clinical data to provide a much-needed overview of the range of issues facing LGBTQ people with mental illness in America.

With the Trump administration demonising both LGBTQ and mentally ill people, this showcase of personal essays, poetry, fiction, visual art could not come at a more crucial time.

Schroeder’s earlier memoir, Beautiful Wreck: Sex, Lies & Suicide, de-tailed her harrowing experience with bipolar disorder and the difficulties she faced in navigating the U.S. mental health system as a lesbian.

Now she and co-editor Teresa Theophano, a licensed clinical social worker at SAGE (Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders), have combined their personal experiences to create this compelling and at times highly unsettling look at how different it is to be dealing with mental illness in a system designed to treat LGBTQ people as already suspect because of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Theophano comes to the work from a different but equally essential perspective. At SAGE, she helps oversee the provision of case management services to older LGBTQ adults and their family caregivers.

She also has a small client caseload and facilitates support groups. So Theophano is immersed in the system from a range of vantage points. It’s a lot—but the breadth of her work has given her a unique perspective.

“As a social worker, a peer— someone living with and receiving treatment for a mental health condition—and a queer writer/editor,” Theophano told me, “I wanted to bring this book into existence because there are so few explorations in the literature of what it means to be out as a queer and/or trans peer.”

Theophano said she thinks it’s crucial that LGBTQ people have peers treat them because the history of how queer and trans people have been treated by the mental health system is so overwhelmingly negative.

She explained, “Our anthology also examines stigma and shame around both LGBTQ identities and living with mental health conditions. We wanted to share a written account of what it means to move through the world with these intersecting identities.”

For Schroeder, the project was an opportunity to address the breadth of the LGBTQ experience within the mental health system.

Schroeder has been part of a veritable underground railroad, whose mission is to help other LGBTQ people with mental illness. Her essay in Headcase details the impact of being denied access to medications, an issue that so many queer and trans people face because the mental health system is often inaccessible to them. Also inaccessible: pricey meds for other various illnesses.

Schroeder talks excitedly about the book as she details how “Headcase evolved into a collection that is groundbreaking in scope. It includes a panoply of literary and artistic approaches to LGBTQ mental health, mental illness, and mental wellness.”

She adds, “Contributors cut across class, race, ethnicity, gender, and age. The book is full of insightful writing and artwork by ‘patients’ and ‘providers’ alike, but without ascribing more authority to one group than the other.”

Theophano illustrates why it was paramount to give voice to LGBTQ people in Headcase. “Many very regressive and very loudmouthed individuals and some institutions still equate homo- and bisexuality and transgender identity with mental illness,” Theophano says. “Headcase includes stories of how this wrongheaded assumption affects our lives, and also touches on how it shows up in the DSM [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual].”

Schroeder and Theophano worked on the book for several years and the result is more than 300 pages of writing from a wildly divergent group of contributors. Some of the art will challenge readers to rethink how they view “invisible” illness; it illustrates the ways in which people suffering from mental illness often feel erased and threatened as a consequence.

For Schroeder, the journey with the book was deeply personal.

She spoke about how working with Theophano “was both overwhelming and amazing. To share such a great responsibility as bringing our voices—38 published pieces—into print with someone who, in the beginning, I didn’t know well, was very humbling,” adding, “Collaborating on the writing is something I had never done before, but it all went surprisingly smoothly, we agreed on everything, and our friendship flourished.”

A project as massive as the one Theophano envisioned made her realise that she couldn’t do it alone.

After she read Schroeder’s memoir, she says, “I knew I had stumbled upon a kindred spirit. I didn’t know how easy the collaboration with her would end up being, or how close our friendship would become.”

She adds, “I feel lucky that someone whose writing resonates this deeply with me is also such a savvy editor and publicist, as well as a truly kind soul.”

Schroeder and Theophano are planning another project together but, Schroeder says, “the time frame is up in the air.” For now, they are working to get Headcase into as many hands and classrooms and libraries as possible. Library Journal gave the book a starred review, noting in part, “The editors intend to start a conversation among LGBTQ people and the therapy community about topics that are usually hidden or ignored. . . They succeed admirably.” Theophano sums up what she and Schroeder want to do for queer and trans people with mental illness, saying, “Many of us are not safe, especially in the current political environment, and we hope to foster better understanding of what queer and trans peers face.”

Schroeder is succinct: “We rarely find personal accounts from LGBTQ folks with mental health concerns. Amplifying our voices on these topics is imperative.”