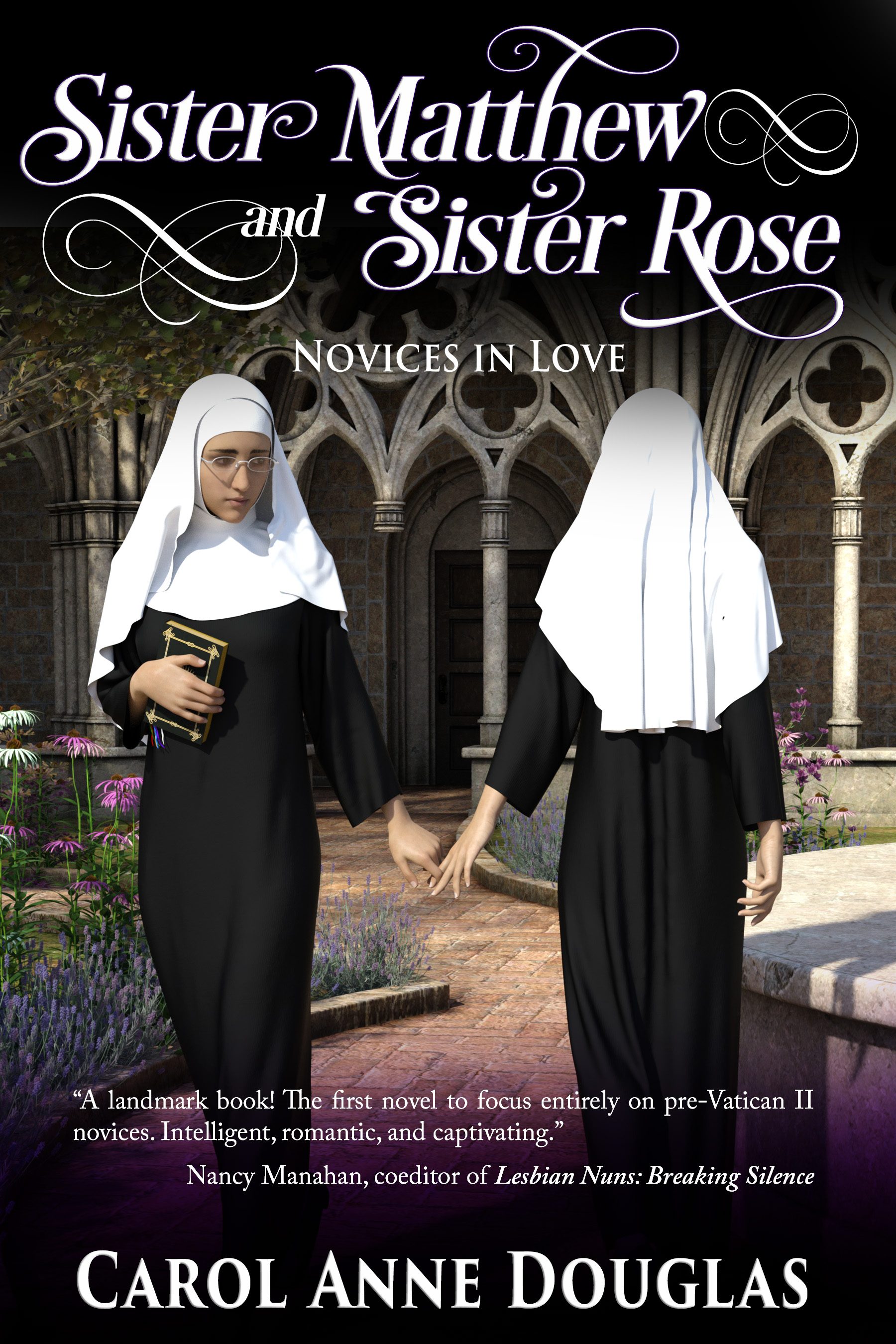

Two women at a convent find love with each other in Douglas’ historical novel, set in the 1960s.

Two women at a convent find love with each other in Douglas’ historical novel, set in the 1960s.

Maureen Collins, recently named Sister Matthew in the novitiate at St. Euphrosnye’s convent in Western Maryland in 1962, doubts the existence of God. She entered the convent for several reasons: she thinks being surrounded by believers might help her believe; she knows she’s attracted to women and wants to avoid pressure to date men and marry, and she feels guilty about something that happened when she was in high school.

She quickly falls in love with Rose Clancy, now Sister Rose, another novice who also is attracted to women. Rose is more religious, but she reciprocates Sister Matthew’s feelings. She grew up with an alcoholic mother and found a refuge among the nuns who taught her.

As the two move through postulancy and the novitiate, they encounter many challenges from the strict rules to memories of their respective pasts. The memory of an old murder intrudes in the present.

We speak to the author Carol Anne Douglas:

How did you decide to write Sister Matthew and Sister Rose: Novices in Love?

I began the book in April 2020. I was becoming depressed by being shut in during the pandemic. I have written several books, so I knew that the way to feel good was to write. This is my pandemic novel.

Did you ever enter a convent?

No. But several friends who entered the convent and left as novices or professed sisters generously shared their experiences with me, which has helped me make the book realistic.

Why did you write a book about women in religious life?

I wanted to write about the feeling of confinement, but not about the pandemic. So I wrote about novices feeling confined in an old-fashioned, pre-Vatican II convent. I went to a private Catholic grade school (1952-1960) and high school (1960-1964), so I was very influenced by nuns. Actually, the word “nuns” is a misnomer because only cloistered women are nuns. Like the one that ran my schools and the order in my novel, teaching orders are not nuns but are called religious. That’s a noun.

My inspiration for this book was a conversation with my friend Nancy Manahan, who co-edited Lesbian Nuns: Breaking silence, a breakthrough anthology published in 1985. She told me that she didn’t believe in God in any traditional sense when she entered the convent. I didn’t either, by the time I was as old as my viewpoint character, twenty-two. So I was fascinated by the idea of writing a novel about a young woman who doesn’t think she believes in God entering a convent to try to develop her spiritual beliefs.

Of course, because I’m a lesbian, I wanted to write about lesbians in the convent during that period.

One of my high school friends entered the order that taught us. After about a year, she was expelled for having lesbian tendencies, not for having an affair. I was angry because it was obvious all the time we were growing up that she had lesbian tendencies. The sisters had tried to separate her from her best friend.

Do you consider yourself a Catholic?

I’m an ex-Catholic. I am, however, very influenced by my Catholic upbringing. Although when I came to doubt the truth of Catholic doctrines as well as being angry at the Church’s position on women’s issues, I am not sorry that I was raised Catholic. I believe that I learned that ethics is important, that how I behave matters, that I don’t have to follow the crowd, that everyone, including people in other countries, matters, and that charity or love is the most important quality to strive for.

Also, I like to say that I’m glad that I experienced living in the Middle Ages. Now the Catholic world I grew up in feels like time travel to another place. That prompted me to write novels about Lancelot as a woman in disguise as a lesbian with a Medieval (but not anti-Semitic) Catholic conscience (Lancelot: Her Story and Lancelot and Guinevere).

What I most dislike about the Church is its history of anti-Semitism, its insane idea that the man it is supposed to revere, and his family and his disciples were Jews, but somehow wasn’t, and that later people who belong to their ethnic group and follow the religion they followed are evil. My main character, Sister Matthew, believes that too. Opposition to anti-Semitism is important to her and there is quite a bit about that in the book.

Because I feel some antagonism to the Roman Catholic Church, I think I bent over backwards to be fair to nuns and priests. I include one nun and one priest who were more progressive than anyone I knew back then because there actually were some who were progressive in that era. In my research for the book, I learned that more than 1,000 priests died in Dachau, so I included that.