Sara Hardy is a playwright, biographer, and former actor. She trained in theatre at Dartington College of Arts, UK, in the mid-1970s and performed with various alternative theatre companies in London – notably Gay Sweatshop (the first professional gay theatre company in Britain).

Sara Hardy is a playwright, biographer, and former actor. She trained in theatre at Dartington College of Arts, UK, in the mid-1970s and performed with various alternative theatre companies in London – notably Gay Sweatshop (the first professional gay theatre company in Britain).

She arrived in Australia in 1981 and, apart from many other things, created lesbian theatre with her partner, Lois Ellis. Sara won the inaugural Peter Blazey Award in 2004 for The Unusual Life of Edna Walling – a biography about the famous Australian landscape designer and creator of Bickleigh Vale Village. Sara’s second biography, Dame Joan Hammond – Love & Music, celebrates the Australian opera singer and golf champion who shared her life with Lolita Marriott.

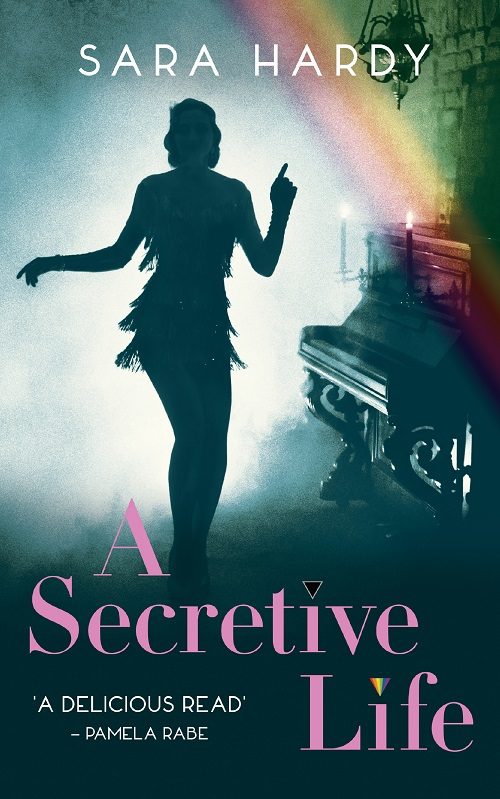

Sara’s newly published novel, A Secretive Life, shines a unique light on the glittering but dangerous LGBTQ+ underworld of the 20th century by telling the story of Cecilia’s adventures, from youth to old age.

Extract from Chapter 1 of A Secretive Life by Sara Hardy:

Call me a fool, but I believe Dolly Wilde’s invitation to view the paintings was a genuine invitation to view the paintings – those more cynical would suggest otherwise. People said unkind things about Dolly in later years – her unpredictable habits soured many friendships, but that evening I was unaware of anything but her radiance.

We took our gin and tonics into the bedroom – and there on the wall were two small paintings by Gerda Wegener.

‘They’re not mine, of course. Dorothy Warren has an art gallery on Maddox Street. She asked me to look after them. They’d close her down if she showed them publicly.’

I’d never seen erotica, and certainly not this sort of erotica. My cheeks boiled with embarrassment. Women’s orb-like bosoms and buttocks and solid thighs. Joyous female to female lust, with the tiniest touch of irony. There was playful energy in the fingers, mouths and even toes, and a jaunty pertness about the sweetly rounded breasts. One woman had an ostrich feather and was tickling her lover’s quiver. I leave you to imagine what the other woman was doing. All this in vibrant colour, the women naked but for a few trinkets and feathers, the decor lush and ornate, the wallpaper beautifully rendered and intricate.

Dolly tilted her head knowingly. ‘Clearly painted for a woman’s eye… Are you shocked?’

I could hardly speak! ‘Just a bit.’ All my feelings for girls and women were Romantic, I didn’t know about the sex part.

‘You don’t like them?’

‘I don’t know. I’ve never seen anything like it before.’

‘I hadn’t either. She captures the fun and joy, but less of the passion, perhaps. She paints them for rich lesbians. The sales keep her going while she’s doing her more serious work.’

The words came out of my mouth before I could snatch them back. ‘What are lesbians?’

Dolly stared at me in amazement. ‘Oh my.’ She extended her languid arm and pointed at the paintings. ‘Those women are enjoying each other, and that is what lesbians do. That’s what I do. You seem a little wobbly – I’m going to make us a nice cup of tea. Come along.’

I followed her meekly into the kitchen, feeling foolish yet relieved to be out of the bedroom. The paintings had made me feel peculiar. Shocked, repulsed, yet strangely enticed. Did women really do such things with each other? The love I had experienced with Leti had been platonic. We had barely kissed. Our love for each other couldn’t possibly be like that. And yet, the proximity of Dolly was making me feel …

She filled the kettle and lit the gas. The flame gave a comforting blue focus as we stood there, I kept my eyes glued to it. ‘We who are happy with ourselves, as in women loving other women, tend to call ourselves lesbians, or Sapphists. The sexologists call us abnormal or invert – but it’s always felt perfectly normal to me!’

She opened different cupboards and finally found the teacups. ‘Sappho was a poet in ancient Greece who frolicked with a lot of women on an island called Lesbos. She was happy and unhappy by turns – and wrote poetry about it.’ Steam began to float from the spout of the kettle and Dolly spooned tea leaves into a pot. Then she looked for a tray. It was obvious she hardly knew where anything was.

‘I hope you’re happy with lemon because there’s no milk.’ She passed me a tin of biscuits and I put some on a plate. Such an easy thing to do, but my hands had lost coordination.

‘I’m not familiar with any of these terms,’ I stammered, ‘and I don’t know what I – how I – how they connect to me.’

‘How can you? These are the words that dare not speak their name. You can’t find answers when you don’t know the question. We’ll sit by the fire.’

She lit the gas fire with a long match. Her lips pursed beautifully as she blew it out. The grill of the fire glowed white to red and made a sort of soft buzzing sound. She poured the tea and dropped a slice of lemon into each cup. Everything seemed so normal, except that it wasn’t, it really wasn’t.

She took another piece of lemon and sucked the fruit from the skin, then licked her lips. ‘I love that tang, so refreshing. Bittersweet, try it.’ But I didn’t.

She sipped her tea.

I sipped my tea, it tasted slightly perfumed. ‘How did you realise … about being a, a Sapphist?’

‘Mother warned me against men so I focussed all my attention on women.’ I must have looked humourlessly blank because she straightaway gave me a better answer. ‘Inclination and curiosity.’

I put my cup down. I didn’t want to sober up.

She said, ‘Oscar Wilde’s name was forbidden in our house – so of course I sought him out. We had boxes of his books in the attic. Oscar believed in the power of love, whatever form love took – and I took that to heart. I fell in love with a girl. We ran away to France at the start of the war and joined an Ambulance Corp. I fell in love with more girls, and so it went on. It’s not so complicated.’ She chewed on another piece of lemon, eating the rind as well this time. ‘And you Cecilia? What of you?’

She moved a stray curl off my cheek and stroked my hair.

I looked into her languorous eyes, they were violet-blue, the pupils strangely large. She raised her eyebrows in expectation of an answer. I knew I was on the edge of a precipice. Step off, I told myself, step off, leap off. I took a deep breath.

‘I look at your beautiful lips and I want to kiss.’ And I leant forward and I did kiss…

All that had been locked down and denied was suddenly shaken free of its weights and shackles. My limbs, my gut, my mouth, my heart all flew towards a terror-stricken sort of bliss.

… And that was the beginning of my Sapphic education.