This Seattle shooter’s queer photo projects have a mission: Get it right.

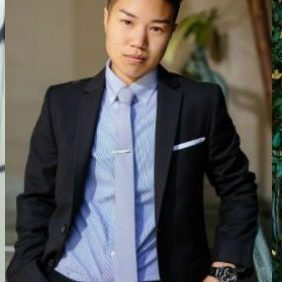

Seattle photographer Molly Landreth went to the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, England, knowing only that she was scheduled to shoot a subject for her Queer Brighton photo project there. She had no idea what he would be wearing or the composition of the shot.

When Brighton teenager Zack showed up in a vintage-style beige-and-white pinstriped suit, accessorized with a small-brimmed straw hat and a double-Albert fob chain, she was a little taken aback. “Do you dress like this every day?” Landreth asked.

“Of course, I don’t,” Zack said. “I’d never wear beige in the winter or fall.”

With Queer Brighton and her ongoing domestic project, Embodiment, Landreth wants to portray LGBT people in their own spaces and lives without allowing preconceptions to get in the way. “The queer community is often underrepresented or misrepresented,” she says. “This project is about getting it right.”

Landreth wants her subjects—ordinary, everyday queer folks from all walks of life—to be her collaborators on each shoot. When she meets them, she does a short interview, and then lets them suggest a location that would make a good backdrop for their life story.

A wardrobe is chosen by the subject as well. Landreth wants them to wear something that will make a statement about who they are. “There’s a performance in all of our lives, and a theatricality,” she says, “especially in the queer community, because we, a lot of us, don’t live life in a mainstream way.”

Are Landreth’s photos natural or theatrical? Are her subjects wearing clothes or costumes? A little of both. Conceptually, Embodiment is about how people are and how they would like to be.

Fashion, according to Landreth, is part of how people tell society their story. “There’s a million different ways that queer people dress,” she says, “so there’s not really a [single] queer fashion.” But her subjects are, of course, making a statement and leaving an impression.

Landreth gets her fair share of surprises from collaborators, like the lesbian couple who dressed in drag as Orthodox Jewish men (costumes from a play they were performing), or the genderqueer man who wore homemade disco ball earrings the size of grapefruits, or the leather-clad biker who talked about her knife collection and her band, Sisters from Hell, during the interview, but on the day of the shoot answered the door in an ankle-length floral dress, having just left a church bake sale.

And there are quieter statements too: crisp jeans, hooded sweatshirts, old coats, bare legs and chests. Even the most casual-seeming arrangements are there to tell the viewer something. The photos in Embodiment are about identity in every sense of the word.

Zack’s unseasonably coloured dandy wear was not the only surprise Landreth got on that Royal Pavilion shoot. The pillar in the photograph is an off-limits area, and no sooner did she shoot the picture than she and Zack were greeted by security. “We set off all the alarms,” she says.