Women have struggled for greater participation in spheres reserved for men in every nation, dating back at least to 620BCE.

Women have struggled for greater participation in spheres reserved for men in every nation, dating back at least to 620BCE.

Yet there is no society on the planet in which women are equally represented in what that society most values and rewards, whether that’s opportunity, money, status or power. This explains the impulse for feminism.

For some, feminism is a theory or ideology about unequal and oppressive gender relations. For most feminists, however, feminism is a political practice – a desire to change the world.

First-wave feminism

Strictly speaking, there were no feminists prior to the invention of the term feminism – in France, in the early 1890s – principally as a synonym for women’s emancipation. The term quickly spread to every continent, in some colonised countries linked with the struggle for freedom from the European colonial yoke.

This phase of feminism is sometimes called “first-wave feminism”, a period during which women struggled for the vote (won first by New Zealand women in 1893, by Australian women in 1901, following South Australia in 1894), entry into university and then into professions like law and medicine, economic independence so women could be freed from “marriage as a trade”, and for mothers’ custody rights to their children.

The second wave

The second efflorescence of activism from the late 1960s has sometimes been called “second wave” feminism. For some so-called “liberal feminists”, their struggle was for women’s social, economic and political equality of access and opportunity, if not outcome.

“Socialist feminists” argued that gender relations, as well as economic relations, had to change. Workers had to be freed from the exploitation of their labour by the owners of big business, and wives had to be freed from the exploitation of their unpaid domestic labour by husbands.

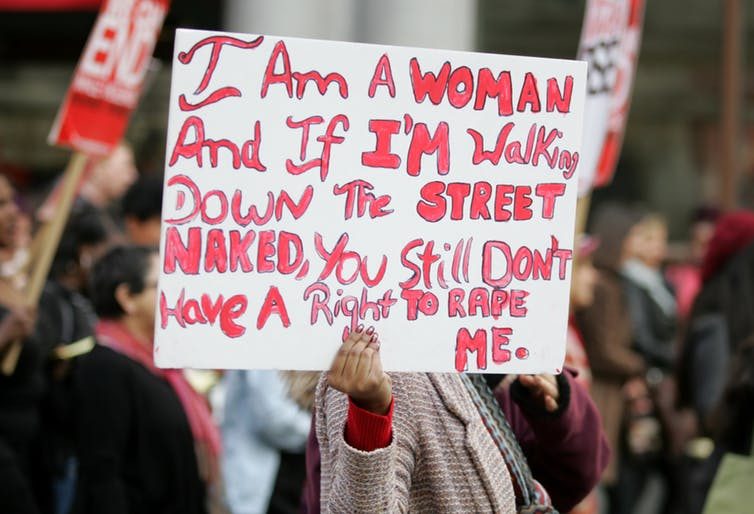

“Women’s liberationists” made a more concerted claim to a woman’s ownership of her own body. Women could determine their own futures if they were released from “compulsory heterosexuality”: won reproductive freedom, social and legal acceptance of lesbianism, access to education and equal pay, an end to sexist stereotyping.

Sometimes called “radical feminism”, American professor of law Catharine MacKinnon claims this is “feminism unmodified”, a feminism that is not moulded to match either liberal capitalism or socialism; feminism which focuses on overthrowing patriarchal relations, those gender relations that make women and femininity inferior, underpaid and exposed to danger from men and masculinity.

The third wave

The “third wave” of young feminists were born into a society transformed by feminist victories: no more legalised discrimination against women, reproductive autonomy, laws against domestic violence and marital rape.

These third-wave feminists shifted their focus from women’s victimisation by male subordination to women’s power to achieve; from women’s freedom from compulsory heterosexuality to women’s pleasure in expressing their sexuality. They shifted the explanation for gender inequality from structural impediments in society to women’s and men’s individual attributes.

Living in the post-feminist era?

By the turn into the 21st century, some commentators claimed we had moved into a “post-feminist” era. This is variously explained as a time when feminism is no longer needed, a time when feminism is no longer active, or a time when feminism has been killed by the conservative neoliberal backlash.

In 2003, Australian author and feminist Anne Summers bemoaned the end of “the national conversation about women’s entitlements and women’s rights”. Conservative governments dismantled gender equality machinery that promoted legislation and policies supporting women’s advancement; media commentators condemned feminist organisations as outdated and unnecessary; women-only services like rape crisis centres, women’s legal services and domestic violence shelters were closed down.

So, how is gender inequality explained in the “postfeminist” age?

Despite regular reporting of statistics that demonstrate women’s inequality, there is a kind of quietude, or belief that women could “make it” if they really wanted to. Ongoing inequality, which cannot be denied and despite over a century of women’s activism, is explained in two major ways.

The “pipeline theory” argues that we are on our way and it’s only a matter of time before women match men in the ministerial, CEO or billionaire stakes. But it will be a long time coming. Take this statistic: there are only 14 women among Australia’s 200 richest people.

Furthermore, there is evidence of retreat. The gap between men’s and women’s average earnings has widened in the last decade and now stands at 18%. The previous federal Labor government had many more women in its ministry than its successor, the Coalition.

The second argument is this: given society is now equal, women and men are just expressing their natural desires and talents when men become CEOs, thoracic surgeons and politicians and women become childcare workers, nurses or full-time carers.

Interestingly this argument is not used to explain male disadvantage. Boys are thought to lose out in schools because of prejudice in the “female-dominated” environment and not because of boys’ lack of interest in learning. Men lose out in divorce battles because of discriminatory legislation and judges, not because of men’s lack of participation in child-rearing. As a result, feminists are accused of crying “victim” where the men’s movement is not.

Gender difference or inequality?

Gender identity is a crucial aspect of how we are in the world. Most of us take pleasure from at least some aspects which might be called “sex stereotypical”: sweaty sports, high heels, cuddling toddlers, fixing the car. Most of us cherish gender differences and yet understand equity and fairness in terms of sameness. And we find it hard to negotiate these complexities.

In a truly post-feminist society, we won’t all be the “same”. But fathers will do as much primary childcare as mothers; mothers will spend equal time in workplaces that are not characterised by bullying and sociopathy.

Women will be prime ministers or chief justices without anyone commenting on their clothes, their unsuitable emotional response to situations or the relationship between their gender and their job. If men still want to be plumbers and engineers and women still predominate among hairdressers and teachers, there will be no significant wage differentials between these jobs.

And no one will ever say, “she asked for it” when she was raped, beaten, murdered or died of hunger – no matter what she did. ![]()

Chilla Bulbeck, Professor Emerita , University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()