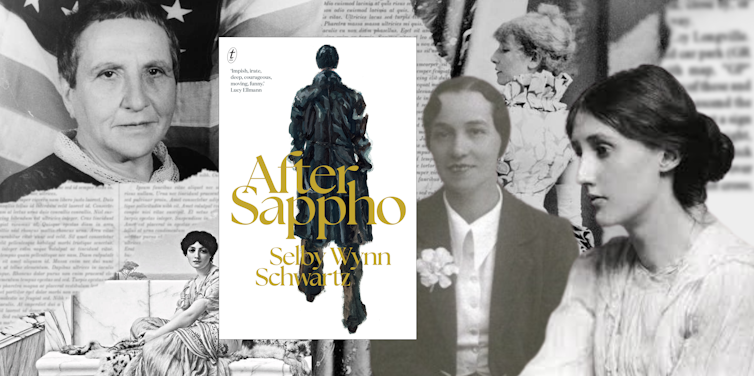

After Sappho, Selby Wynn Schwartz’s reimagining of the lives of 19th and 20th-century women artists, activists and sapphists is a book I’ve always wanted to read. (And it’s just been longlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize.)

Francesca Rendle-Short, RMIT University

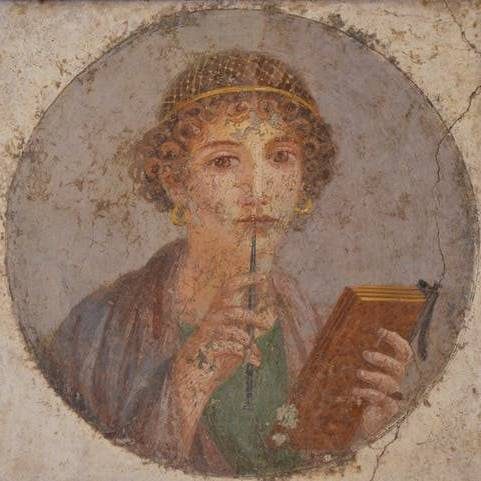

Sappho, an Ancient Greek poet from the island of Lesbos, was often called “the Poetess”. Plato called her the tenth Muse. Her writing is intimate, lyrical and sensual. It is unapologetically erotic and primarily directed towards women. She’s been called history’s first lesbian.

Who among us lesbians hasn’t wanted to be loved by Sappho or in the Sapphic way? To be Sappho — as in, as Wynn Schwartz writes in the prologue, “inside ourselves”, “sky pouring over”, “leaves of trees shivering”, “everything trembling”, “move when nothing touches”; as in the Sapphic fragment “the opposite/ … daring”?

I remember the first time I became Sappho too.

Review: After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz (Text Publishing)

A novel in fragments

After Sappho is a novel in fragments or cascading vignettes, it rolls like water, like waves, introducing the reader to numerous feminists, writers, sapphists, activists and artists from the late 19th and 20th centuries. Through their work and how they determine to live their own lives, they carve out a way to take control, become themselves, and inspire others to do the same.

The book’s narrative adopts the plural first-person “we” or collective voice, binding us as a community of readers to the pioneering poetry of Sappho and these brilliant women. They followed, showing us how to live. We become part of the chorus line, the voices that will never be silenced.

At first read, I was a little shy; I thought I needed to know everyone and everything before meeting them: a bit like coming out, I needed to demonstrate a solid sense of the self. Bite by bite, Wynn Schwartz introduces us to her characters, folding them together and into us: she lets their voices “wing their way through”; rise on our tongues.

In this work are the sapphistories of herstorical figures we know well. There’s Radclyffe Hall, Sarah Bernhardt, Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf – along with lesser-knowns such as Ada Bricktop Smith, who in 1924 learned what it was like to black up her face (when she was already a black girl) to earn a living, and Eileen Gray, who in the 1920s as an avant-garde artist, writer and architect, opened a gallery of her own, full of light and lacquer and glass.

Difficult-to-read counternarrative moments intersect these herstories. Such as the story of the Italian poet, playwright and feminist Lina Poletti (said to be one of Italy’s first openly declared lesbians) giving the poet Rainer Maria Rilke an unfinished draft of a play she had written. She wrote Arianna at a time when she and her lover, the great actress Eleonora Duse, were “almost winged”. (Poletti and Duse lived with each other for a time; Rilke was obsessed with Duse.) Rilke declared, “she wanted too much; her Ariadne was too many things at once”. Poletti suspected Rilke was “lying through his teeth”.

And Noel Pemberton Billing’s Black Book (compiled by the British Secret Service, by reports from German agents), listing every lesbian in Britain (although by law they didn’t exist), and denouncing “lesbian ecstasy” and the Cult of the Clitoris – is it “an unsteadiness in hand”, is it a “trembling in the mouth”? Moments like this plunge any “careful becoming” back centuries, “into history we had barely survived”.

A prescient book for our times

This book is prescient, written for our times. It’s not just a critical re-writing/righting of herstory, or a new view on queer feminists in turn-of-the-century Europe. It’s a warning, and a light shone forward, posing an old question we are still asking, especially with the recent Supreme Court overturning of Roe v. Wade in the US.

As Italian suffragist and businesswoman Eugenia Rasponi argued hotly in 1914, more than 100 years ago: “We are still denying women the right to their bodies? It is as if the new century has changed nothing.” Fellow Italian feminist (and writer) Sibilla Aleramo explains: that it’s not democracy but tyranny.

Dotted throughout this novel is the everywoman Cassandra, who was famously fated to tell the truth, but never be believed. She appears in different periods in this novel, a lantern-bearer and prophetess, modelled by Wynn Schwartz on the Trojan priestess and the poet Anne Carson and her poem “Cassandra Float Can” (from her collection, Float). Cassandra is also a figure in Virginia Woolf’s writing; she invented a “Cassandra for 1914” to counter the madness of war; Cassandra lights the way to a different kind of future.

We need a modern-day Cassandra, a Cassandra for our time who can scream outside of language, “gash the fabric of normal life, to rend it into strange tatters”. The point and impulse of language is everywhere. A Cassandra who lives in her future. It is time for women to take language for themselves, as Gertrude Stein argues:

it confuses, it shows, it is, it looks, it likes it as it is, and this makes what is seen as it is seen.

Each short section of After Sappho, each following fragment, juxtaposes a new day. A further revelation is “scattershot relief against a landscape”. Wynn Schwartz gives us a grammar of becoming that touches all surfaces “like flash powder”; a kaleidoscope of pleasure; a seeking of verb and tense, shifts and changes.

She brings together her purposefully arranged fragments of herstory of this time and these fierce women to give us hope “of becoming in all our forms and genres”. She tells us, “The future of Sappho shall be us.”

And there we are, among these wonderful foremothers, in first-person plural around the table – you know that game, of wishing guests to a slow degustation. The same table that brings Vita and Virginia together for the first time when Vita breaks in to get Virginia’s attention: “I think you are Sappho of our time.” We will never be silenced.

‘Speak desires aloud and inspire’

This is a book in verb and body, a novel of many parts – it’s fun thinking of its genre (fun writing a review in fragments) – a hybrid of “imaginaries and intimate nonfictions”, “a composition as explanation”, “an alchemical experiment”. In this novel, characters are tracked across pages and different years: some come to the page as more of a sketch (like a first draft) and build up as they return; others appear fully formed from when we first meet them.

Writing this review happened in the pages and margins of the book itself: a jot here, underlinings, arrows, transcription, X X X against passages for extra emphasis. There was so much to remark upon, and absorb; my imaginaries interlocking with those on the page.

After Sappho is an unstructured community where everyone is equal and this community imbues a spirit of its own: a heady fountain of what can happen in the space of togetherness itself, in which the “blush of our inner parts” turn “out towards each other”. Where, as inverts and delinquents, lesbians and viragos, we want to be “everything at once” and believe “this is possible”. Wynn Schwartz invites us to this Sapphic community: right here, right now. “Life itself”, present tense. Where we congregate, speak desires aloud and inspire.

After Sappho is an ecstatic read, a sapphistory writing ourselves into existence into the lives we want to live – not the lives others want us to live. It is a provocation to become who we want to become. The women in this wondrous novel, a tour de Sappho, are our foremothers, our foresapphists. Birds fly out of its pages.

Selby Wynn Schwartz gives us dark herstory; one that is hysterically funny, poetic and maddeningly tender. It is skin and sinew and breath and longing. And becoming. Remember to tongue it slowly.![]()

Francesca Rendle-Short, Professor, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.