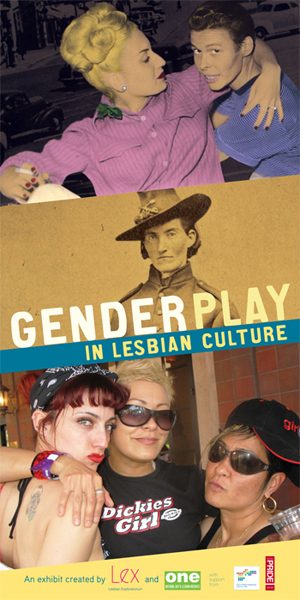

GenderPlay in Lesbian Culture, now at the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, aims to show that lesbians have been playing with gender for over 100 years – from Calamity Jane to Rachel Maddow.

GenderPlay in Lesbian Culture, now at the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, aims to show that lesbians have been playing with gender for over 100 years – from Calamity Jane to Rachel Maddow.

Producer Jeanne Cordova and curator Lynn Ballen give us the inside scoop.

There is a group of lesbians in Los Angeles standing at the intersection of gender and sexuality and surveying the terrain. The Lesbian Exploratorium Project’s (LEX) latest exhibit, GenderPlay in Lesbian Culture, now showing at Los Angeles’ ONE Archive, is a testament to the individuals who have stood outside the normative gender binary, from Calamity Jane and the estimated 400 female soldiers who passed as men to fight in the Civil War, to MSNBC’s newest media darling, Rachel Maddow. Produced and curated by LEX members Jeanne Cordova, a veteran lesbian activist and former publisher of the Lesbian Tide, and Lynn Ballen, the exhibit brings together hundreds of historic and cultural artifacts that show how gender has been defined over generations and how it might be defined in the future.

What was the impetus behind the show? How did you think through what you wanted to include?

Lynn Ballen: Well, Jeanne has a long time history as an activist and an organizer and also a publisher, in the gay and lesbian community. We had formed this group, LEX out of a group of friends who were writers and filmmakers and activists, all of whom are really eager to have more lesbian cultural events in Los Angeles. We started off with the inspiration—there’s a slideshow about passing women, there was one put together by the, I think she was the editor of the Lesbian Tide at the time. And there was also…[one] put together up in San Francisco, though the San Francisco Historical Society, I believe.

So, that was sort of the beginning of the idea, and when we sat down with—we pulled together about 15 women and had sort of the first mixed brainstorming session…and I mentioned this personal fascination with the passing-women concept as, like, a beginning of something. Everyone jumped on it because it fits so well with where genderqueer and gender identity is going right now. And so we sort of filled in the blanks; we created a story arc from there.

Jeanne Cordova: Yeah, I think when we had gone places and seen the younger generation and what they are doing with gender was also inspiring. We wanted to have some sort of event where the lesbian feminist generation and the queer young women could meet each other and exchange ideas. The older ones would find out where the kids are at and why, and where they’re going. And the kids would find out how the older generation kind of started the movement.

It does seem to me that you guys are trying to start that dialogue between lesbians of different generations.

Ballen: Yeah, and that was really important to us.

What do you hope they’ll take from it?

Cordova: Oh, I hope that the older lesbian feminist generation…learn that they are not the only definition of lesbians out there. That it was an era and feminism still lives on, but they need to see what the kids are doing, specifically with their gender and politics. And then the young people need to see that they didn’t pop up like toast from anywhere and that a lot of people paid a lot, especially in the other generations, you know, in the Civil War and in the ’40s and ’50s, when lesbians were killed for being lesbians. And, we wanted to show them that. That they walk on hallowed ground, that they should feel part of a very long family tree.

Why was it important to include first-person accounts?

Cordova: That was Lynn’s idea.

Ballen: Yeah, I think it was really to give voice to these women—I found that there was sort of pieces of history in all different places and there’re some amazing anthologies…some great academic history books, but it was very hard to find all of this in one place.

Cordova: I think the other reason I heard you say…was that feminism often looks to the personal experience of the individual to tell the historical story. Rather than give you a third-person narrative—“Well this is the way it was, blah, blah, blah,”—which is much more removed. And I think people learn best by getting emotionally up close to an individual and hearing their story.

Did you find it difficult to find evidence of gender playback as far as the Civil War?

Ballen: Yeah, there was some writing and research done by, initially a woman who was a civil war reenactor who was kicked out because she was a woman dressed as a man, from a civil war reenactment of the battle of Antietam. So anyway, she went and did research on at least 150 women who were known to have passed. And then [there were] personal letters, diaries, anecdotes that were passed down, so they estimate at least 400.

Cordova: Another thing that surprised me is that a number of photos are from straight libraries, like the Boston Public Library or the New York Public Library. There’s not a lot of this kind of material in the lesbian and gay archives, and when there is they’re kind of not organized enough to get their hands on it. So you can go and get it and put it on the Internet, and as an archivist, I found that kind of interesting, that our archives really need funding.

You mentioned before that you created the arc of a storyline through the years the exhibit covers—where do you think that story is going?

Cordova: It seems clear that one’s body is now an option to be looked at or changed. I think that technological advance wasn’t there 20 years ago. So that brings in a whole new set of options to young queer kids that we didn’t have. And young people can go on an exploration.

I think there will be gay people and lesbians—there always have been, so there always will be. I’m not one of those lesbian feminists who’re overly threatened that a lot of young lesbians might want to become guys. When I was younger an awful lot of straight women came into the lesbian movement because of the politics, the women’s movement—then, I would say, 10 to 15 per cent of them decided, “Well I’m heterosexual.” They got more in touch with who they were after the political emphasis was over, and I see the same thing [happening] with trans people. There are a number of women who think they are lesbians who really are transgender and they want to pursue that to a total extent or a half extent or whatever. But I don’t see that as threatening to the integrity of the lesbian community. That probably always was, there were women in my generation who would have liked to have switched out. I welcome the trans kids, and I think that is one of the natural continuums of being gay and lesbian: questioning gender.

Ballen: And the minute we take a step into being lesbians, we’re questioning gender roles anyway. So it’s at that intersection of gender and sexuality, a crossroads.

You’ve said that you think that every lesbian has visited that intersection at some point, whether or not she’s aware of it or not.

Cordova: I really do. I think once you decide that you’re gay, you’ve stepped away from the gender norm even if you’re femme or a butch guy because you’re sleeping with [someone of the] same gender, and you’re also having different feelings and doing different things. I think femme lesbians are very different to straight women. You know, having slept with both a lot I can tell from personal experience, they’re really different. [Laughs] And so, I think all femmes and all androgynous and butch lesbians, just by virtue of that, trying to have a relationship, you stumble into, “How are we going to work out having a relationship in terms of the male-female continuum? Where are we going to divide things? How are we going to work it?”

Ballen: I joke that straight people will be grateful to us that we’ve worked this out for them now. It gave them more permission to play with gender roles.

Cordova: It already has. I think the gay movement has significantly changed what heterosexuals are in terms of roles. And even what it means to be men—I think the women have changed that because I see today’s young men, both gay and straight, and they’re nothing like the macho men of the ’50s and ’60s. The sexism that was so endemic to men of my generation—me being 60—is totally different. These young guys are so much less sexist and so much more willing, it feels to me, and they see women as their peers.

Do you think gender play is becoming more mainstream? Has it lost its political power?

Cordova: I don’t think so. Because it seems to me that we are talking about different issues than about gay liberation and lesbian liberation and, you know, civil rights. I think the question today is more pinpointed around one’s body and gender specifically. We never consciously played with gender in any parts of the movement I was in during the lesbian feminist ’70s or ’80s, and I think the lipstick lesbians were not consciously playing with gender. I think they were kind of playing with assimilation and celebrity and all those things. So, I do think that the questions have been raised more concretely today and they’ve gone much further. I mean, we have lesbian photographers like Cathy Opie getting into the Guggenheim with her outrageous genderqueer stuff. And to me, gender play might be just be breaking into the mainstream. I don’t think it has gone mainstream yet. I think like Opie is an exception and, you know, lipstick lesbian chick and The L Word and all that has been mainstreamed, but I don’t think queerness has been mainstreamed. Look at Rachel Maddow, who is a present-day phenomenon. You know, somebody even said, “She might be a new gender on television.”

Who said that?

Ballen: Oh, it was Helen Boyd of My Husband Betty.

Will the exhibit be showing anywhere other than ONE Archive?

Cordova: Yeah, we’re open to that and we’ve designed it in such a way as it could be shipped pretty easily.

Tell me about the Lesbian Exploratorium Project.

Cordova: For right now we decided that we didn’t want to become a nonprofit organization and get wrapped up in bureaucracy, which inevitably happens once you do that. We wanted to become a kind of a zap action squad that produced or participated in lesbian culture, made things happen more in Los Angeles.

So, for our first project, we built a lesbian wall that will be unveiled at ONE Archive in August. It’s a big wall, designed by the collage artist Cathy Cade, that’s made up of covers of lesbian publications. It spans 60 years, from 1948 to 2008. So, that’s the kind of thing we do. We see an opening or someone is willing—especially if they’re an organized group—and they say, “We want lesbian content.” Well, we’re the content.

GenderPlay in Lesbian Culture runs for two months, March 14 to May 23 at the ONE Archives Gallery & Museum at 626 N. Robertson Blvd. in West Hollywood. It is proudly co-produced by LEX and the ONE Gay & Lesbian Archives, with co-sponsorship from the City of West Hollywood and LA Pride/Christopher St. West.