A production of A property of the clan that holds contemporary relevance in a society where a culture of violence against women still persists.

A key piece of writing for Australian youth in the 90s, A Property of the Clan is a powerful and emotionally candid examination into peer pressure by one of Australia’s pre-eminent playwrights, Nick Enright. In 1997, the play was adapted into the Australian drama thriller film, Blackrock.

A disturbing tale inspired by real events, A Property of the Clan tells the story of the sexual assault and murder of a 14-year-old girl at a party. It examines a culture of boys and girls lost in the misrepresentation of one another, the ugliness of victim-blaming and the emotional and social effects the unexpected death of a peer has on young people.

The story follows a small group of teens including Jared who witnessed the crime, his girlfriend Rachel and best friend Ricko, and the victim’s best friend Jade. Torn apart by the tragic event, the group delves into why it happened, who is responsible and if justice will be served.

In a bold staging concept, A Property of the Clan will see the performers both create and destroy the set during the show. On a Perspex backdrop, the performers will paint their childhood memories before tearing it down at the end, symbolising the loss of innocence experienced from the terrible crime.

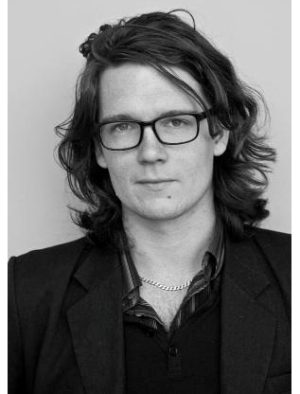

The production holds contemporary relevance, particularly with increasing exposure on the issue of violence against women in the community today. A Property of the Clan examines the psychology of victim-blaming. LOTL spoke to director Phillip Rouse to discuss the play and its exploration of social issues:

What drew you to the story of ‘A Property of the Clan’?

It feels much bigger than an earnest Australian Drama. It works like a myth. Ricko, our God of Masculinity, comes to town and causes havoc, which the human beings left behind have to grapple with. In metaphoric terms, after the death of Tracy, the rest of the play is spent in awe of God’s Masculinity and Grief. We see teenagers and adults alike constantly butting against their inability to emotionally cope with what has happened. The other thing that drew me to the story is that while the criminals are brought to justice, the world doesn’t change. That even an event that is as horrific as the rape and murder of a 14-year-old girl cannot create any real shift in their society. That was a very important truth that drew me to the show.

What are the most difficult things to consider in regard to the direction of a play, and how is this influenced by what you want the audience to take away from the production?

Avoiding cliché is probably the trickiest thing about this production. Because basically every character is implicated in the terrible crime either through direct action or a lack of direct action, no one in this play is wholly good. But as a director I want my audience to empathise with their struggles without going easy on them. I want the audience to honestly identify in themselves when they haven’t spoken out, or weren’t brave enough, or were and the great things that happened when they did. That requires a lot of honesty on my part as a director and confronting my own flaws around this issue. It’s a delicate balancing act.

In your opinion, why is ‘victim blaming’ so common?

That is an enormous question. For me, the base pathology of it is if men haven’t done anything wrong (or their crime is the lesser crime) then nothing needs to change about society. We have built a critical framework where men become the hapless victims of the woman’s indiscretions, her failure to fit into a conservative blueprint of what it means to be female, and thus he wouldn’t have acted how he acted if she didn’t act how she acted. We put yet another horrible act away in a box and the machine keeps ticking over. It’s culturally institutionalised bullying. And it is fucked beyond belief.

Have any of your personal beliefs been unexpectedly challenged in the process?

When looking at this material as a straight white male, and especially while reflecting upon your teenage years, realising how much you were in the thrall of this conservative blueprint can really take you by surprise. You want to believe you are a good person, but maybe that wasn’t always the case. The process of shedding damaging notions of masculinity (particularly attitude towards women) is a long one and one not every male goes through it. And in working on this play, if forces you to engage with attitudes you have shed and admit you understand them from the inside. That is what I mean by being honest as a director.

Director: Phillip Rouse; Assistant director: Anne Brito; Executive producer: Stephen Carnell; Stage manager: Bronte Axom; Designer: Martelle Hunt.

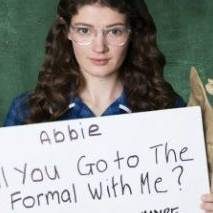

A Property of the Clan includes Sydney Theatre Awards 2014 winner George Banders (All’s Well that Ends Well, Romeo & Juliet), Megan Drury (Ruben Guthrie, Macquarie, Closer), Jack Starkey-Gill (Bell Shakespeare’s Players’ Company) and Samantha Young (Vampire Lesbians of Sodom, Space Cats).