Fame and appreciation come and go like the tide – one day they’re in, the next they’re out. Patricia Highsmith is no exception and after some years’ ebb following the success of The Talented Mr Ripley, the tide is again on the turn.

Fame and appreciation come and go like the tide – one day they’re in, the next they’re out. Patricia Highsmith is no exception and after some years’ ebb following the success of The Talented Mr Ripley, the tide is again on the turn.

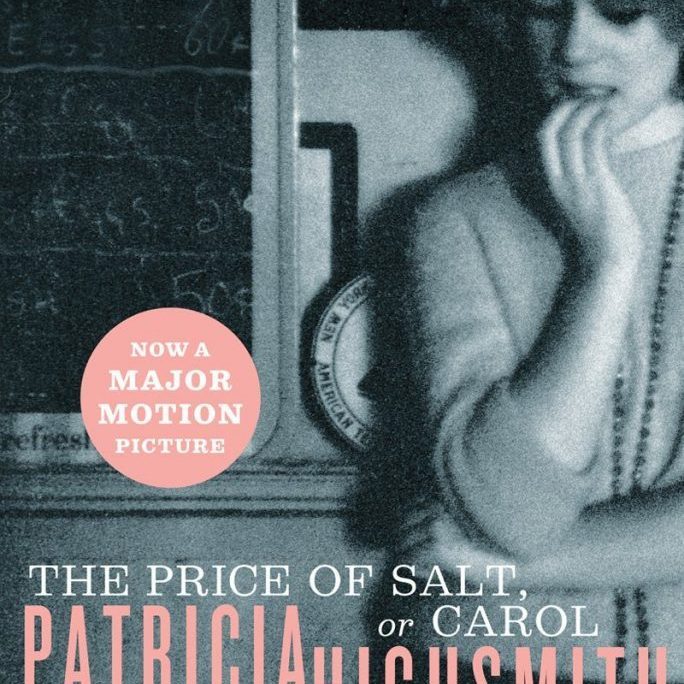

This can be divined by two clues: first, the much-anticipated cinema release in 2015 of Carol, based on Highsmith’s 1952 novel The Price of Salt, with Cate Blanchett in the title role and Rooney Mara as her younger lover.

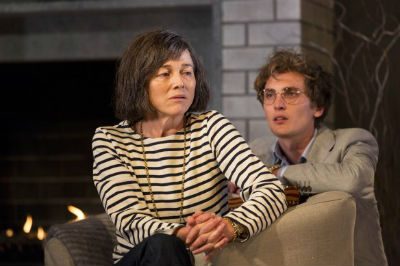

The second is Australian playwright Joanna Murray-Smith’s commission by the Sydney Theatre Company and Geffen Playhouse to write a play “about” the celebrated misanthrope. Titled Switzerland, it’s playing to full houses throughout November and December at the Sydney Opera House Drama Theatre and opens in Los Angeles early 2015.

Starring the remarkable New Zealander Sarah Peirse, Switzerland is an imagining of the last three days of the author’s life when Edward, a young editor from her New York publisher, arrives at her home in the land of cuckoo clocks and muesli to persuade her to write another Ripley book.

Aside from the daring of inventing a life for such a notorious figure, Murray-Smith has succeeded in channeling one of 20th century literature’s most distinctively acerbic voices. For instance, as Pat is baiting Edward, she says of his foolishly mentioned wish to write,

“Jesus H Christ! If you want to write: write. Don’t ask me for permission. I so absolutely do not want you to write. The world is full of people who should be actively discouraged from taking pen to paper. Discouraged as in forcibly restrained if necessary. Or even physically assaulted. Whatever it takes!”

Then, when he questions the idea of an early morning beer, she snarls, “Of course it’s perfectly possible there is a Swiss law forbidding the personal consumption of beer in your own home at 8am – because they’re not generally mad bon vivants. No beer, no thank you, no, I’ll go jogging and then I’ll read a self-help book and eat some broccoli so that I have an excellent thirty years sitting immobile but with pumping heart in a nursing home, desperately wishing but unable to express the desire for someone to put a plastic bag over my head because I can’t remember the words for plastic bag.”

It succinctly encompasses Highsmith’s penchant for fun at someone else’s expense and her lifelong delight in the macabre and her ability to shock – also evident in a discussion they have about murder:

“Don’t you ever ask yourself: What would it be like? I don’t think there’s a human being alive who hasn’t wanted to slay. We hate with a passion just that bit more robustly than we love. But what sorts the wheat from the chaff is who will act? Who has the guts to cross that line?”

These are the questions Highsmith returns to over and over in her novels; and not just with Ripley – in oblique ways too. Carol, a wayward and wilful bourgeois, not only has the guts to cross the lines of 1950s middle-American mores by leaving husband, child and home for a younger woman, but also goads her lower class lover into the adventure – a real transgression.

And in Switzerland, Joanna Murray-Smith has Highsmith being goaded by the young Edward to cross the lines of polite society by poking her with one incendiary word: “Mailer” and the question, “Doesn’t it bother you that he called you a high-class detective novelist?”

As Germaine Greer and Gloria Steinem – so the fictional Highsmith also explodes: “Detective novels! Was Crime and Punishment crime fiction? I write about life. Life as it is, no sugar added. I’m ugly at heart, so what? We all are. That’s what makes us more interesting than rocks …The American literary establishment? … a bunch of middle-aged male writers with massive pretensions and a desire to write their individuality on the world in ink…Death is everything: the summation of life, its point, its resolve, life’s permanent and irrevocable foil. And I’m rather good at writing about it. So Norman Mailer can go fuck himself. Drink?”

The more things change, the more they stay the same.