White Americans, like Kelly, must learn the full and accurate history of the Civil War.

Boston-born White House chief of staff John Kelly’s recent remark on Laura Ingraham’s new Fox News show reopened a divide so deep in this country about slavery that I am reminded of American novelist William Faulkner’s quote “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Kelly told the conservative media television host that he viewed Confederate general Robert E. Lee as “an honourable man” and that “the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War.”

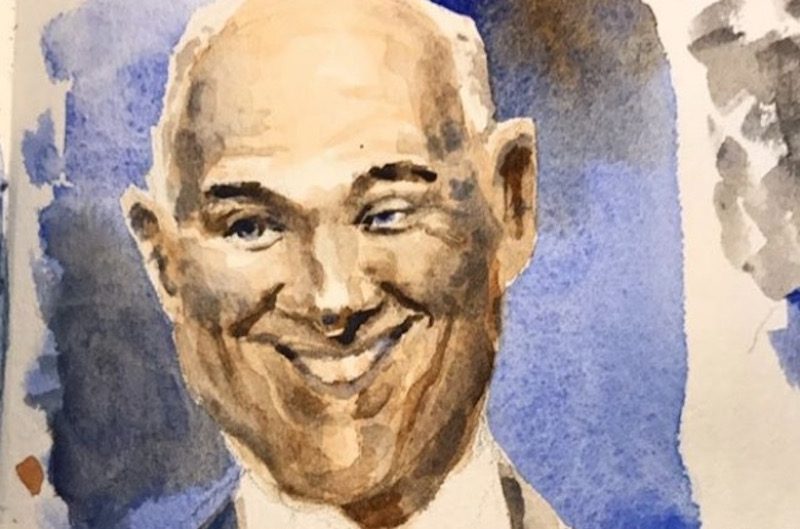

The moral relativism of Kelly’s statement suggests there’s no absolute truth about the war, only truths that a particular individual or culture upholds. But Kelly is wrong! And, Keith Boykin, an African American gay activist, and CNN political commentator challenged Kelly’s absurdity in a tweet.

Slavery is America’s original sin many of our venerated Founding Fathers’ were wealthy slaveholders. Slavery was a brutal history of deliberately debasing and dehumanizing enslaved Blacks. And, because the horrors of slavery are told mostly from a white and/or heteronormative perspective like Kelly’s, the suffering of enslaved LGBTQ Africans goes invisible. These stories, however, are gradually coming out of the closets of African American oral histories and are fictionalized in the literary works of Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone, Courtney Milan’s The Pursuit Of, Alyssa Cole’s That Could Be Enough, and Toni Morrison’s Beloved, to name a few.

For example, the “slave buck” in oral history and literature is commonly known as a breeder. However, knowledge of white gay slave owners forcibly having sex or raping male slaves—straight or queer—isn’t. And, while the stereotype of the “docile slave” was a mythology to emasculate black manhood the depiction was also coded to signal to slave owners that black males might actually be queer.

John Kelly, a retired four-star general, needs a history lesson on the Civil War, period. And, he should start with LGBTQs whose lives are seldom mentioned. For example, queer Civil War buffs have been arguing for some time that the deafening silence around LGBTQ Confederate and Union soldiers suggests their very presence.

When shots were fired at Fort Sumter, a fortification near Charleston, S.C., signalling the war’s beginning, its gay Confederate and Union soldiers weren’t battling the infamous DADT policy or Trump’s now-rescinded band on transgender service members. And, those soldiers unlike ours today neither had to bare their souls to disprove that military readiness is a heterosexual calling nor did they have to prove that their patriotism to the cause was somewhat diminished because of their sexual orientation.

And, it is estimated that approximately 325,000 of us out of 3,250,000 were on the battlefield if we go with our present-day queer census that one Confederate or Union soldier in ten falls in our camp. Some queer Civil War buffs would argue that none were dishonourably discharged albeit there is a record of three pairs of Navy sailors court-martialed for “improper and indecent intercourse with each other.” But the question, I surmise Kelly would argue, of who were LGBTQ service members and who weren’t in the Civil War is a disingenuous query since the words “homosexual” and “heterosexual” weren’t part of the American lexicon until thirty years after the war ended.

However, many would also argue that not having an “official” word like “homosexual” back in the day of the Civil War to depict same-sex attraction among soldiers does not negate our use of it to describe them in this present day. And in combing through Civil War battle records of Confederate and Union soldiers, I find, they were not only slaughtering each other – many were also loving each other.

Learning about same-sex love among soldiers wasn’t Thomas P. Lowry’s focus when he sat out to the pen, “The Story the Soldiers Wouldn’t Tell: Sex in the Civil War,” the first scholarly study of the sex lives of soldiers in the Civil War.

If Kelly knew his Civil War history he would know that when the war ended Robert E. Lee refused to be buried in his Confederate uniform and asked followers to put their flags away because displaying them as a form of defiance would be an act of treason. Similarly, Robert E. Lee, V, the great-great-grandson, made a similar request about the statues. “If it can avoid any days like this past Saturday in Charlottesville, then take them down today,” he told the Washington Post in August.

White Americans, like Kelly, must learn the full and accurate history of the Civil War. Otherwise, they compromise the nation’s ability to move forward.