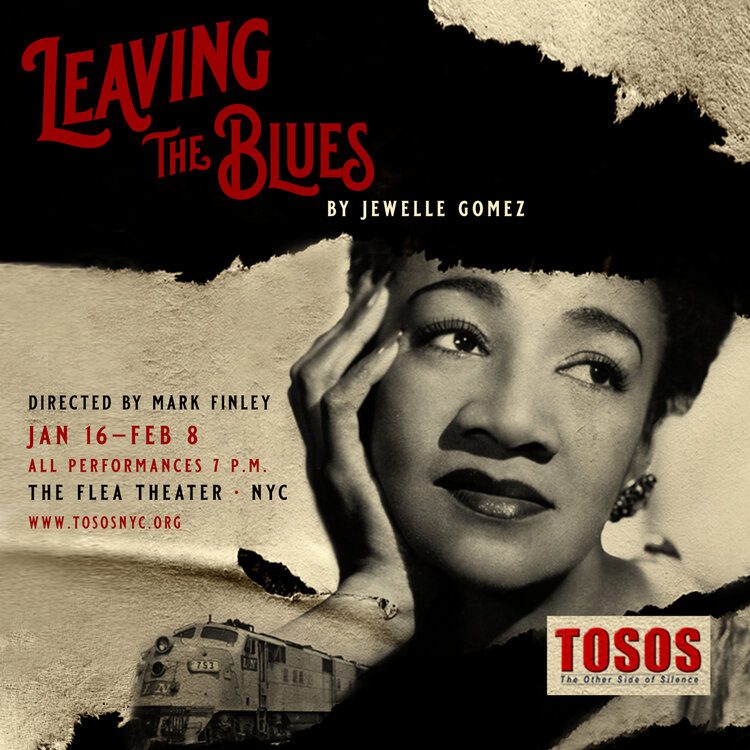

A new play by Jewelle Gomez puts the life of lesbian blues singer Alberta Hunter on stage for the first time.

The great American jazz singer and songwriter Alberta Hunter is almost all but forgotten today outside of students of black history or music — but she was one of the great black female entertainers of her time, along with Josephine Baker, Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters, Billie Holliday, Bessie Smith, and Gladys Bentley — who were also lesbian or bisexual.

Hunter, however, was much more closeted than her colleagues and this, arguably, ironically, impacted her personal life, if not her career.

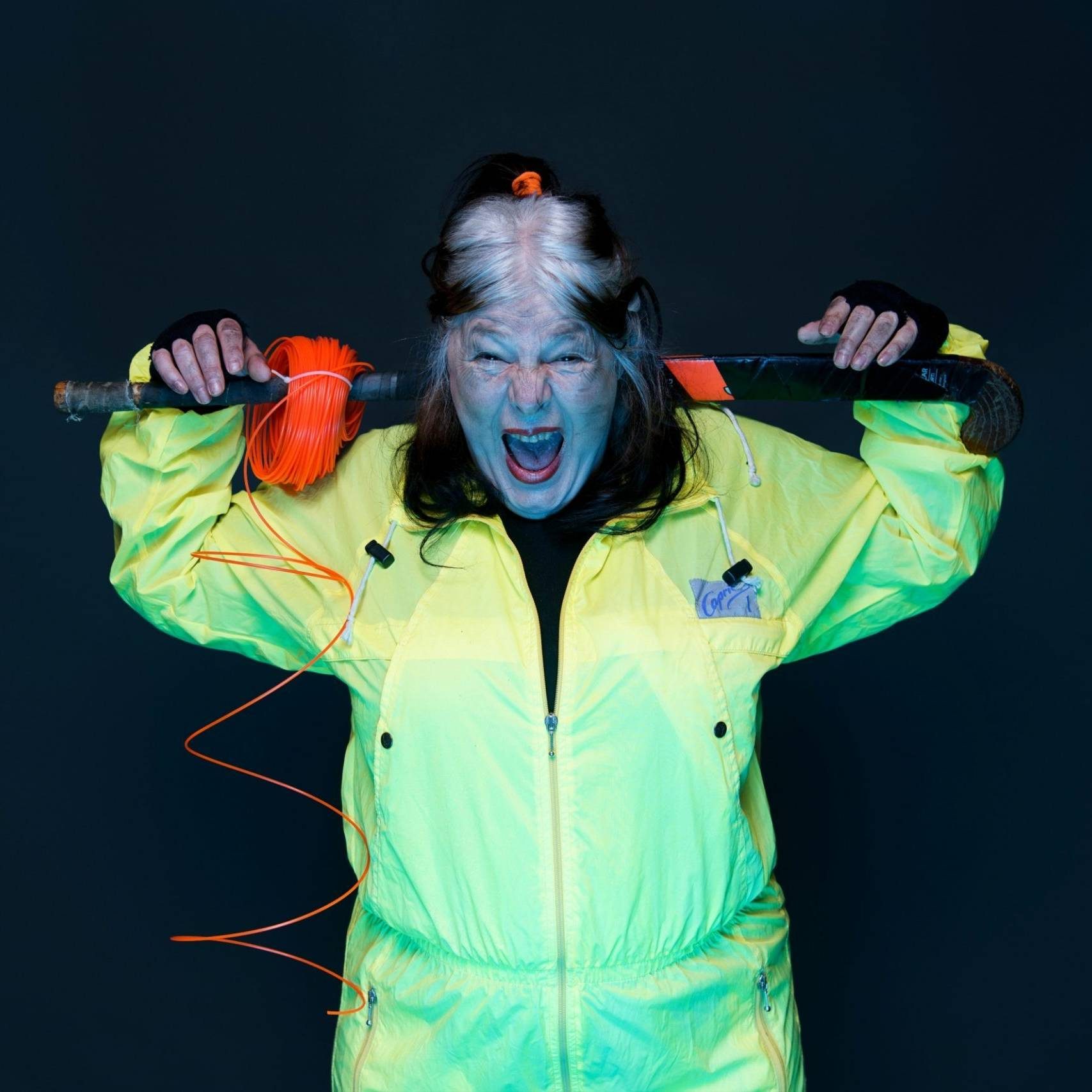

Alberta Hunter is the subject of Leaving the Blues, a new play by lesbian author and playwright Jewelle Gomez. Gomez, who is 71, saw Hunter perform live at The Cookery in Greenwich Village in the 1980s several times and she noticed in the audience many lesbians who had come to see Hunter because they had heard that she was a lesbian.

According to Gomez, Hunter (a marvellous portrayal by talented singer/actor Rosalind Brown) was “ladylike, sassy, risque, but in a kind of Victorian way.” Although she was indeed a lesbian and had a great love with another African-American woman named Lettie (played with elegance by Joy Sudduth), Hunter was prim and in the closet for her entire life.

Gomez was intrigued. There was a gay woman who lived through incredibly turbulent times and survived, enjoying a comeback when she was well into her 80s. Gomez had written a play about James Baldwin and started thinking deeply about African-American artists of the early 20th century and their struggles and sacrifices.

“Alberta came back to me as one of those people who had a lot of hope and energy and I really wanted to see where I could go with her,” Gomez tells me.

This two-act, eight-actor, multi-character drama with songs is a stunner, redolent with musical numbers, behind-the-scenes jealousies, sexual tension, deception, sacrifice and uncertainty. It begins with Hunter, aged 82, being sacked from her job in a nursing home, and flashes back to her heyday as a popular singer, and the choices she made in her private life that fed into her fame, fortune, and (un)happiness.

The play is produced by the award-winning theatre company TOSOS (The Other Side Of Silence), New York City’s oldest and longest producing professional LGBTQ+ theatre company, which also produced Gomez’s Waiting for Giovanni, about James Baldwin, written with Harry Waters, Jr., last year.

Jewelle Gomez is the author of eight books including the Lambda Award-winning classic, The Gilda Stories, which is about black lesbian vampires. Gomez found that there was very little written about Hunter, and while many people know her name there was only one biography, sparse papers, and a few clips on YouTube — unlike James Baldwin, who wrote volumes and had volumes written about him.

“I thought it would be very challenging for me to create a character that is only halfway known,” says Gomez. Why Hunter slipped from history had something to do with the 1950s and changing tastes — with people preferring Doris Day or black women who looked white (Lena Horne) or sounded white (Ella Fitzgerald). It wasn’t until film director Robert Altman asked Hunter to do the music for one of his films that people’s memory of her was “energized,” says Gomez.

Hunter’s skin was dark and she sang the types of songs that didn’t automatically cross over into the white mainstream taste. At that time, Gomez says that black women who were accepted or successful in the entertainment industry, whether singers or chorus girls “had to be light and bright.”

Thankfully, colourism is a theme in Leaving the Blues. It was an issue for Hunter and it’s something Gomez has experienced in her own life — within the African-American community and her own family. As for Hunter, she was appreciated as talented even though she was “dusky.”

In some ways, Hunter was too much for the culture. There is a history of subjecting black women — from Whitney Houston to Lizzo — to unreasonable standards, whether of excellence or beauty. “I know what society does to black women if they don’t stay in the place they want us to be put,” says Gomez. “We inherit a lot of that colourism and homophobia and self-hatred around who we are; the dominant society pressures our community and then our community pressures us.”

Gomez cites Lizzo after she performed on Saturday Night Live, who had her appearance attacked by online trolls judging her to be overweight and therefore unhealthy, despite the fact that she could sing and dance for over an hour and barely be out of breath.

I ask Gomez whether or not our culture has gone backwards, because at one time it seems that there was space for larger-than-life black entertainers to perform for adoring mainstream audiences: Gomez agrees and cites Patti LaBelle and the Blue Belles as “one of the wildest, outrageous, talented African-American groups to ever take the stage.”

“Sometimes it seems as if we have the full array of black female talent just flaring out into the world and then at other times it seems that everyone is trying to come up with something else that’s popular, to see their way towards riches. You have to be groomed and shaped if you want to fit into a crossover,” says Gomez.

While Hunter was popular in the first part of the 20th century during the Harlem Renaissance, after the war tastes were changing and becoming more conservative, as indicated by the rising popularity of Doris Day. Ella Fitzgerald was also popular, but “she was kind of like Mel Torme. They both had perfect pitch and happy voices,” notes Gomez. “Which is beautiful, but it’s easily more popular than what we used to call gut-bucket music.” That music dealt with everything from the spiritual, to the existential, to the carnal, such as the Bessie Smith classic “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out.” Or, take the saucy, gutsy lyrics to Hunter’s own hit, “My Handy Man”:

Now whoever said a good man is hard to find

Now whoever said a good man is hard to find

Positively absolutely sure was blind

Cause I just found the best man that ever was

And here’s just a few of the things that he does

He shakes my ashes

Greases my griddle

Churns my butter

And he strokes my fiddle

My man, is such a handy man

Now he threads my needle

And he creams my wheat

Heats my heater

And he chops my meat (he’s a mess)

My man, is such a handy man…

Leaving the Blues features the songs sung by Hunter as well as a new, original song written by Toshi Reagon, “Lettie’s Blues.”

I won’t spoil the context of that piece, but it ties in with the play’s themes. Gomez cites Hunter’s challenges as a dramatic character: “Is she gonna be able to figure out how to make Lettie happy?

Is she going to be able to make it in this world when people are against her? Is she going to be able to find the strength she needs?”

As a playwright, Gomez brings back and makes space for two forgotten lesbians: Alberta and Lettie. “We’ve got to see them,” she says. “And how many times do you see old women on stage?

As a Baby Boomer myself, I feel like we’re still here and vibrant, but people have weird imaginations about who old women are. We stand as signposts for people coming after us. The reality is Alberta and Lettie did break up. But they always stayed close and they always checked up with each other. Women can support each other and care about each other no matter what.”

We can, and we do. Do your bit. Go see Leaving the Blues.