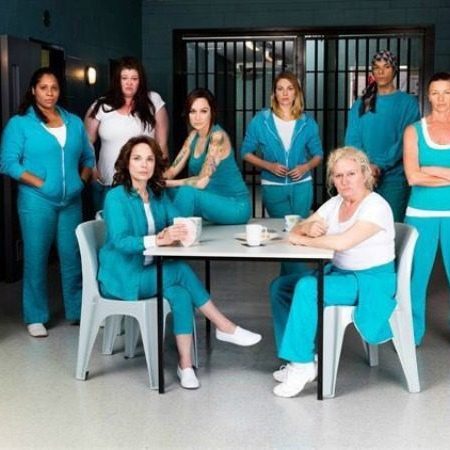

Any Australian lesbian worth her salt is at least aware of actress Libby Tanner.

Libby Tanner stole our hearts in 1996 as the first woman to partake of a lesbian kiss on mainstream Australian TV, as the gay character Zoe in Pacific Drive. As Nurse Bronwyn Craig in All Saints, she not only won two Silver Logies, but she also locked lips more than once with Tammy McIntosh’s lesbian character, Dr Charlotte Beaumont.

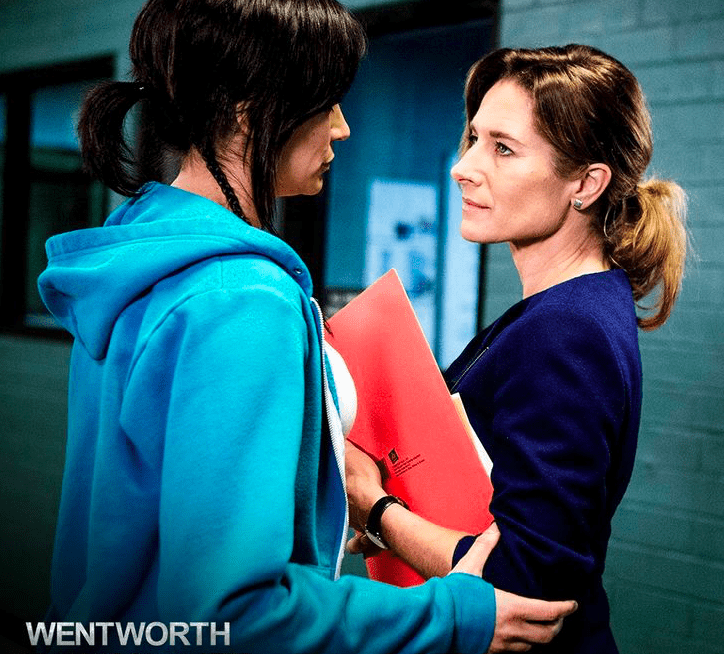

But fast forward to the present and I am compelled to ask: Who hasn’t fallen in love with Tanner’s most recent character, Forensic Psychologist Bridget Westfall, in Foxtel’s Wentworth? I know I certainly have!

Her line,

“Yes, I am a lesbian… now can we move on?” is delivered so matter-of-factly thaton the one hand I was beyond excited to hear these words spoken on TV, while on the other, the utter normality of it would make it difficult for any naysayers to even have time to register. Much of Bridget’s appeal lies in the fact she’s not a stereotype, she’s not a trope, and she’s not driven solely by her sexuality.

Libby Tanner has a habit of bringing us these characters, comfortably representing the lesbian that doesn’t get squeezed into the stereotypes of hard-core butch,

predator or criminal. Tanner has a loyal and long-serving lesbian following, which is one of the reasons why it is so exciting to see her back in theatre and on the stage in the hilarious production of Abigail’s Party, by iconic UK playwright Mike Leigh.

Before there were yuppies, there was Beverly and Laurence Moss – an upwardly mobile couple living in London in the late 1970s.

Beverly, masterfully played by the wondrous Tanner, is the ultimate hostess with the mostess, as she nags and bites at her boring and overworked husband Laurence, played by Brad Beales, while holding a welcome soiree for recent arrivals to the neighbourhood Ange (Rose Sejean) and Tony (Richard Sutherland).

Add to the mix the divorced and nervous Sue (Kethly Unikitty), whose 15-year- old daughter Abigail is having a raucous party at her house nearby, and a cocktail of one-upmanship, discontent and drunken, debauched flirtation appears inevitable. The humour lies in the “ouch factor” as the characters became increasingly intoxicated and their lips increasingly loose.

Of all the characters, audiences would most recognise Tanner’s Beverly – at once sexy and sanguine, but combined with a need to subtly bully and belittle those around her to ensure her position as the ‘Queen Bee” of the soiree, and indeed of the street.

Beverly is stuck in a loveless marriage to a man who is ‘dead below the waist’ and, in the teenage party being thrown by Abigail, and the hunky former professional soccer player Tone, she sees an opportunity to grasp onto a moment of her bygone youth.

The physicality of Tanner in bringing Beverly alive is much of what drives the humour, as does Sutherland’s seemingly simple-minded hunk Tone, whose extreme masculinity is rather disconcerting, but also highly amusing. Beverly’s and Tone’s dirty dancing, together with her insistence on playing Feliciano, because “nobody wants to listen to classical music at a party Laurence” is both hilarious and cringe-worthy at the same time. It is impossible not to laugh at their antics as their mutual ogling becomes more lewd and salacious.

It was obvious that the actors were enjoying the characters and the story, and the unbridled laughter from an audience totally immersed in 1970s kitsch and the scurrilous behaviour of these wonderful characters was refreshing. Personally – I haven’t belly-laughed like that in the longest time, and I loved every second of this wonderfully funny, delightfully black show.