The documentary ‘Love, Cecil’ explores the life of Cecil Beaton, including his affair with lesbian icon Greta Garbo.

While we may assume that queer identity is a contemporary phenomenon, the 20th century saw its fair share of queer trailblazers who shaped the century in art, design, and culture. One of the most successful and memorable queer creators was Cecil Beaton, the British photographer and designer whose life’s work consisted of numerous portraits of English royalty, gods and goddesses of the silver screen, 30 books on beauty and aesthetics, including his extensive diaries, countless articles and images for publications such as Vogue, and scenic and costume design for stage and screen.

The self-taught artist and polymath was a trans-continental phenomenon for over 50 years. Even if you don’t know, you will have seen his innovative portraiture capturing other queer icons such as Greta Garbo, Katharine Hepburn and Marlene Dietrich, and enjoyed the lush spectacles he created for classic Hollywood films such as My Fair Lady and Gigi.

A new documentary, Love, Cecil, screened at the Telluride Film Festival and at DOC NYC, the largest documentary film festival in the United States, which is where I saw it. But now it’s due to open in New York City on June 29, and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in queer history.

Directed by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, whose previous work includes documentaries on fashion legend Diana Vreeland (her grandmother-in-law) and art collector and socialite Peggy Guggenheim, Love, Cecil is a reminder of the vital contribution made to culture by gays and lesbians.

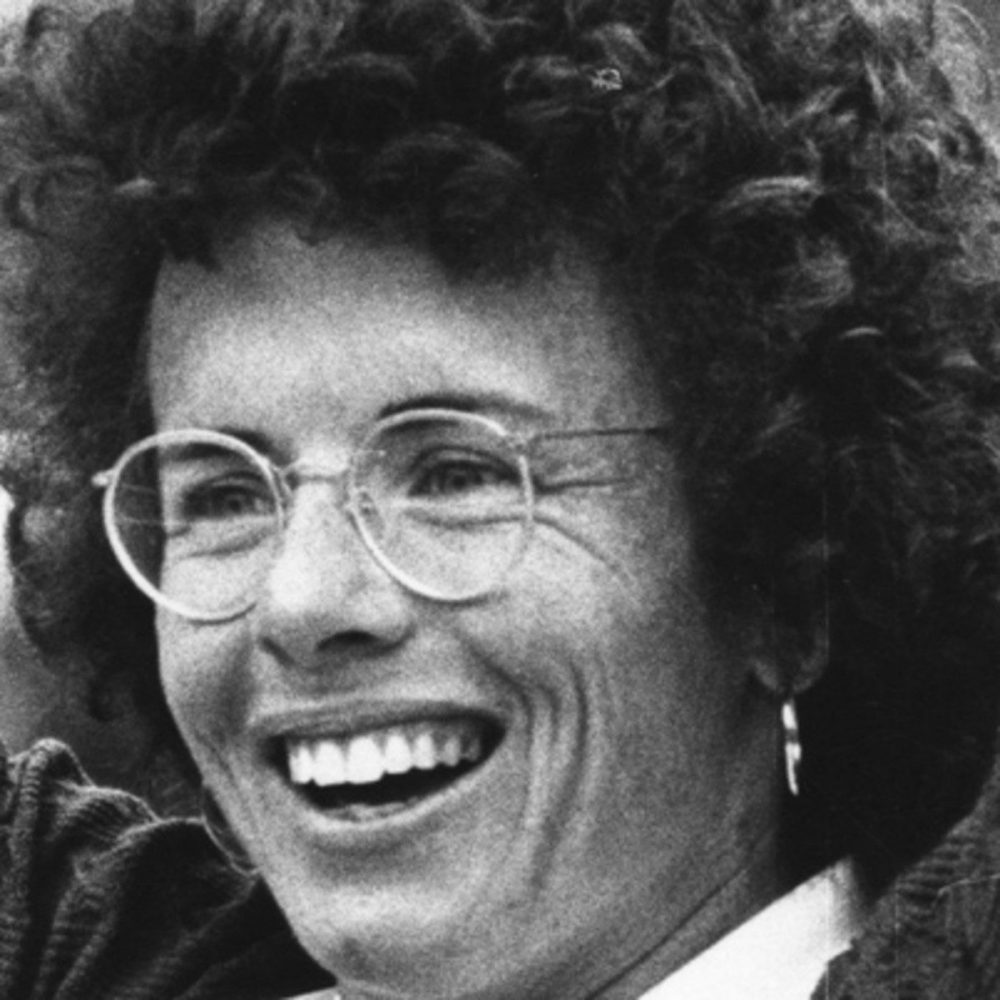

Though Beaton described himself as “a terrible homosexualist,” he was obsessed with women from a very early age, collecting photos of cross-dressing female theatre stars, teaching himself photography by practising on his sisters, and angling to photograph aristocratic women and even film legend Greta Garbo, for whom he harboured a life-long infatuation. When he died in 1980, three photos were found in his bedroom: two of his male lover and one of Garbo.

Narrated by out actor Rupert Everett, Love, Cecil is a treat for lovers of the visual arts. It’s also a testament to how a singular, marginal identity pursued to its limit can transport an LGBT sensibility into mass culture. Despite—or perhaps because of his homosexuality and eccentricities—Beaton elevated photography, which was still a relatively new form beyond photojournalism and conventional portraiture, combining a taste for the avant-garde with his almost feminine appreciation of beauty.

The film beautifully organises the rich artistic legacy of Beaton and turns it into a moving quest for self. Beaton’s talents are not only on display; we also get to relish his irrepressible wit and unapologetically acid tongue. For example, he wasn’t a fan of Katharine Hepburn, who he photographed when she played Coco Chanel on Broadway, declaring that she was about as beautiful as “an old boot.”

While lesbians will disagree with that estimation, we can agree with his adoration of Greta Garbo. The film touches on their affair, which may or may not have been sexual. The actress Leslie Caron muses that there probably was some “hanky panky” between them, and perhaps we’ll never know.

But we know that Beaton took a series of striking portraits of the reclusive screen icon under the pretence of producing a passport photo for her. He went on to publish the images in Vogue, much to her disapproval. Beaton’s work also had its severe side: he was a war photographer, chronicling Britain’s involvement in the devastation of World War II, and I,t is thought that his heartrending images, which were published in Life magazine, did an excellent deal in getting America on board as a military ally.

His portraits of Queen Elizabeth II helped establish her as a rightful royal.

One of the strengths of Love, Cecil is that the film doesn’t shy away from Beaton’s flaws and disappointments. He was somewhat of a social climber, chronically unsuccessful in love, and so involved in his processes he didn’t seem to be aware of his infringement on the feelings of others.

While he was possibly a narcissist, he states unequivocally that he was never vain. He seems to have been driven by feelings of inadequacy. Perhaps if he were alive today, he would be an Instagram influencer. He certainly has been influential on several gay male creators, such as David Hockney and Isaac Mizrahi, who give onscreen commentary on Beaton’s impact on their outlook.

But it’s more likely that Beaton was a unique product of his time when England was defined by class structures when Europe and America were greatly influenced by each other. Trans-Atlantic crossings led to a cross-pollination of cultures. Beaton’s work mirrors and amplifies the 20th century’s waves of innovation that led to an unfolding sequence of unique decades.

Throughout his life, Beaton expressed his queer sensibility outwardly, holding lavish parties, participating in salons, and taking experimental self-portraits in drag. He partly celebrated the often androgynous allure of his subjects. His portraits of women tend to express their strength and complexity rather than diminish or objectify them, as later fashion photographers have done. And in addition to his outrageous flair for performance and deception, he helped pioneer mid-century photojournalism.

Love, Cecil is compelling viewing, especially for anyone who is different and feels at odds with the mainstream—and wishes to have a lasting impact on it anyway.