It’s 1959, and Vivian, an immaculately manicured and tightly controlled English literature professor from Columbia University, is arriving in Reno, Nevada, to stay on her friend Frances’ ranch while waiting for her divorce to come through.

Prospective divorcees have to be resident in Nevada for six weeks: long enough for Vivian to fall in love with casino change-girl and artist Cay, a friend of the family. It’s the beginning of an awakening.

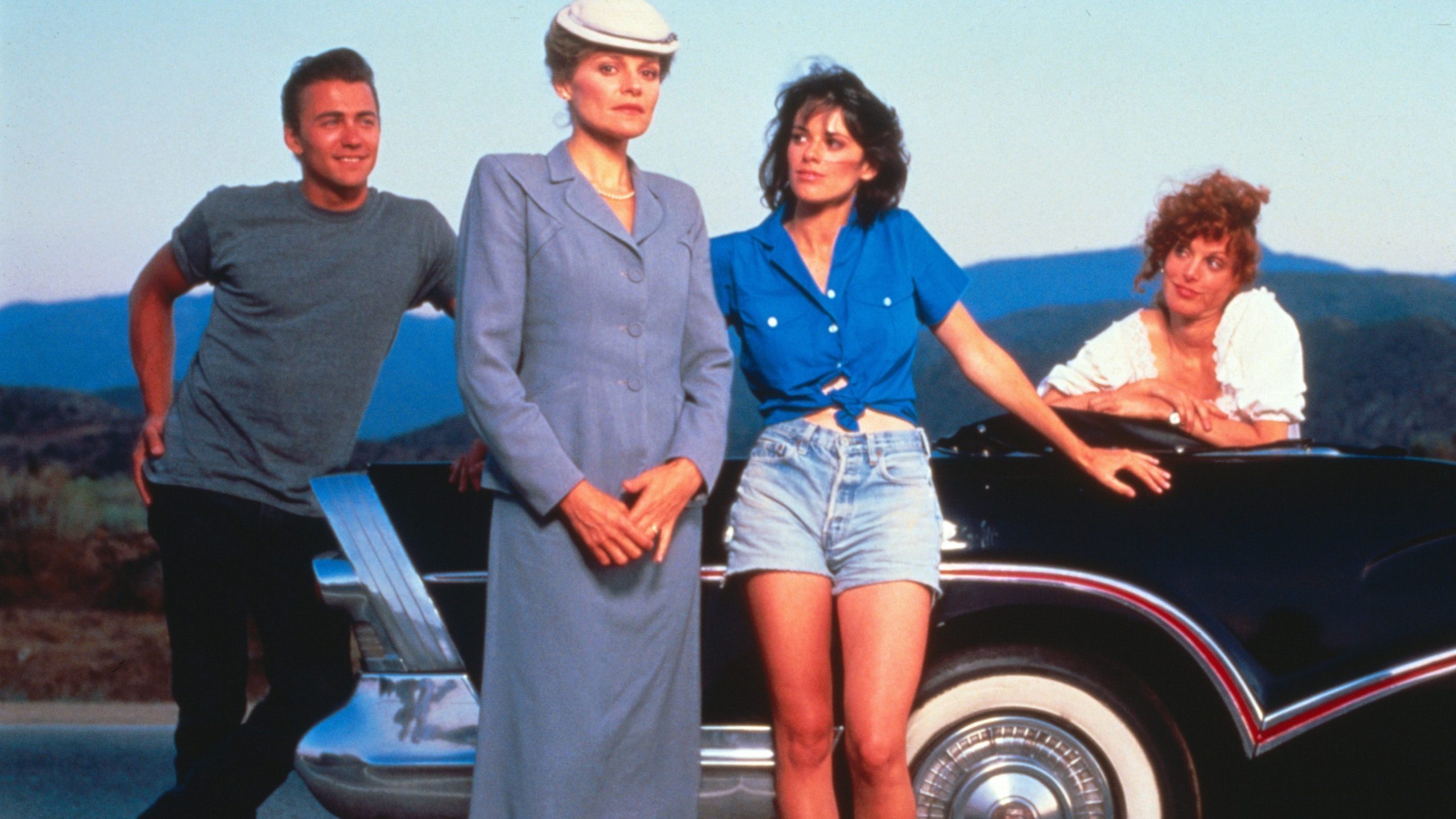

This is Desert Hearts, a 1986 film with striking parallels to last year’s hit Carol. First shown 30 years ago at London’s first gay and lesbian film festival, it returned this year to BFI Flare, serving up a heady mix of 1950s rock ‘n’ roll, casinos, cowboys, and lesbians. The success of Carol and the return of Desert Hearts reflects our need for stories that show not only the difficulties, hostility and discrimination faced by lesbians but also offer up the possibility of honesty and love.

In recent years, several important lesbian films have both impressed critics and found box office success. Blue is the Warmest Colour (2013) is probably the best known of these – an intense story of first love and the pain of a relationship’s breakdown.

The Kids Are All Right (2010) was perhaps more unusual, about a long-established lesbian relationship and the challenges of bringing up children and staying in love. Lesbian films have become more mainstream since Desert Hearts was first released, but the film remains relevant today.

Desert Hearts was not an easy film to make. In the mid-1980s, director Donna Deitch sold her house to pay for the rights to the film’s soundtrack: Elvis Presley, Patsy Cline, Buddy Holly, Johnny Cash. Deitch had already raised a lot of the money to fund it herself. Casting agents told her no established film actresses would audition for the parts of Vivian or Cay.

Yet in 1986, the film got a glowing write-up in the Guardian “because it makes neither the usual appeal for tolerance nor proselytises”. Deitch said that she didn’t want to make an overtly political film; she wanted to make one “that didn’t end in a suicide or two suicides or a bisexual triangle”, one where you were “positively rooting for [the main characters] to be together at the end of the film”.

But this was, of course, a political choice in itself. To set up the narrative so that we end up hoping that the two women can find a way, to be honest with each other and themselves was a profoundly radical – and political – act. Deitch was, after all, making the film in the wake of the dramatic women’s liberation movement, which insisted that “the personal is political”.

The films Desert Hearts took as its counterpoint were works like Personal Best, Robert Towne’s 1982 movie about track athletes, which implied lesbianism was just a “phase”. Or The Killing of Sister George, a British production from 1968 in which Beryl Reid played an unpleasant, masculinised lesbian who bullied, molested and seduced her way through the film. Desert Hearts is none of these things: intense, wild, as strange and lovely as the Nevada desert.

When Desert Hearts first came out in 1986, Steve Jenkins wrote in Monthly Film Bulletin that the film failed to evoke the hostility lesbians faced in the 1950s. This seems unfair for two reasons. First, Cay might be comfortable with her sexuality and find acceptance among her friends, but she certainly experiences hostility and rejection – not least from Frances, who is, to all intents, her stepmother, but who struggles to see her sexuality as anything other than unnatural and disgusting.

The idea that 1950s America was an implacably hostile and violent environment in which to be gay also obscures as well as reveals. Gay liberation had been underway in the US for over 15 years by the time Desert Hearts came out – ever since the Stonewall riots of 1969. But the explosive power of gay pride could sometimes obscure the fact that life was not always unrelentingly bleak and lonely for men and women who desired the same sex in the years before 1969.

Desert Hearts gives a glimpse of the other side of the picture – it shows us unprejudiced characters, even in 1950s Nevada. There’s Cay’s best friend Silver, or the ranch-hand who jokes with Cay: “How you get all that traffic with no equipment beats me.” It is in this that the film, despite being 30 years old, is similar to last year’s Carol, for which Rooney Mara and Cate Blanchett were both nominated for Oscars. Carol, too, showed us quietly confident lesbians. It was one of Foucault’s great insights that the very persecution of a sexual minority could give that minority a heightened sense of identity and community.

Both films are based on books written in the 1950s and early 1960s – Desert of the Heart, by Jane Rule, published in 1964, and The Price of Salt, by Patricia Highsmith, published in 1952. Highsmith published under a pseudonym to avoid drawing criticism. Rule’s position as a lecturer came under threat because of the publication of the book. Yet despite the climate of homophobia in which they wrote, both were determined to write stories where lesbian characters were given the possibility of a happy ending.

And the need for lesbian love stories that aren’t doomed is just as great now as it was in 1952, 1964, or 1986. Rule, Highsmith and Deitch all anticipated our contemporary yearning for authenticity, self-expression and truthfulness. That is what makes these books and films so compelling and relevant today.

Director Deitch is currently fundraising for a “sequel” to Desert Hearts, to be set in Manhattan during the intense period of the women’s liberation movement, which was divided in the US – often quite viciously – over the issue of lesbianism. If it’s half as good as Desert Hearts, it’ll be worth watching.

Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, Lecturer in History, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.