At a time of increasing threats to basic civic decency, the acceptance of LGBTIQ rights, as they are often called, has become a comfort blanket for progressively-minded people.

In the year following the marriage debate, it is not surprising that the Melbourne International Film Festival chose The Coming Back Out Ball as their closing night gala event.

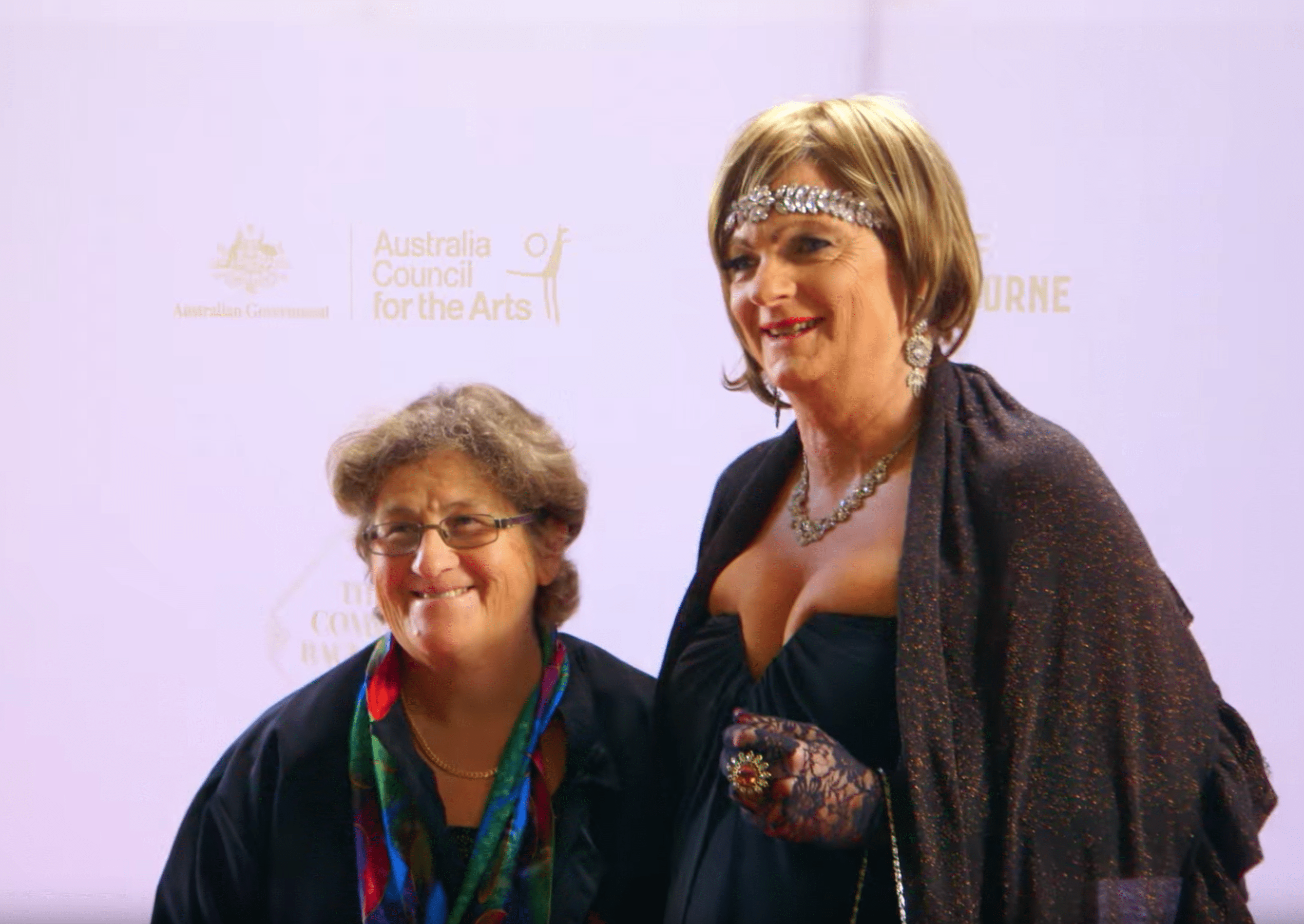

The Coming Back Out Ball is a documentary of an event of the same name held in October 2017 in the Melbourne Town Hall. It aimed to include and honour elders of the LGBTIQ community. (The indigenous use of “elder” is increasingly used in queer political circles.) It was an extraordinary event, attended by hundreds of people — for those in the community over 65 it was free — which combined dinner, dancing and a floorshow compered by Robyn Archer.

Gay Alcorn wrote in a long and loving account of the Ball:

They arrived in sequins and feathers, six-inch heels and pancake makeup. They arrived, too, in T-shirts and hiking boots, frocking up for no one. There were walking sticks and wheelchairs, a blind man with a guide dog, a woman with a shirt saying “This is what an old lesbian looks like”. This was their night, and they’d come as they please.

The film sets out to show the lead up to the Ball, but particularly to tell the story of 12 of the “elders” whose stories helped inspire a younger generation to organise the event. Central to this story is the performance artist Tristan Meecham, who over several years worked with his collaborator Bec Reid to provide space for queer elders to join together in social dancing.

Tristan and Bec appear briefly in the film, but I left wanting to know much more about what drove Tristan to become such a central figure in creating a remarkable institution, one that says a lot about the city and state governments as well as the richness of queer cultural life in Melbourne.

The film concentrates largely on a group of older lesbians, gay men, one transwoman and one intersex person, all of whom tell stories of living their lives under the shadow of ignorance, self-denial and sometimes persecution. A couple of the women in particular are remarkable characters, lightening up the screen by the sheer force of their personality.

But the problem with trying to tell social history through individual stories is that it can only capture certain strands. One of the men referred to a partner long dead from AIDS. The only long lasting partnerships depicted are two heterosexual marriages, one between two people who conveniently both discovered their homosexual desires and separated amicably, the other a transwoman whose marriage has been stretched by her transition at the age of 60.

There are plenty of older lesbians and gay men living in very long established relationships, but we do not see them.

Unconsciously the film reproduces some of the sillier claims of the marriage movement, that only with legal recognition could queers form committed lifelong partnerships.

At least one of the women in the film has a long history of activism, as her flamboyant t-shirts make clear, but political agency is denied in the stories, except for a couple of passing clips from early gay liberation protests. The film tells us that things have become easier for those of us who live outside the heterosexual norm; it makes no attempt to tell us why.

Yet many of the early activists were at the Ball that evening, and it would have been easy to have spoken with some of them. Strong as the personalities on film are, they almost all reinforced a certain monolithic picture of victimhood and concealment that suits the progressive narrative.

There have been several Australian cinemographic attempts to capture the changes in attitudes towards sexual and gender fluidity in the past year. Jeffery Walker’s film Riot focused on a very different story, namely the Gay and Lesbian Pride Parade in Sydney in 1978 which led to massive police reaction, and became the basis for the city’s Mardi Gras. Riot was of course a very political film, but again one that told the story of queer progress through the lives of a few individuals, making a couple far more significant than they actually were at the time.

Telling the story of social and political change requires key individuals with whom we can identify, and I applaud the makers of The Coming Back Out Ball for using people who are not already well known.

But this device also risks oversimplification, and painting an anodyne picture of history. The underlying message of The Coming Back Out Ball seems to be that now we can all find our authentic selves, and perhaps live happily ever after, if not necessarily for very long.

This assumes that there is an authentic self, and that political progress allows us the freedom to find our “true identity”. Yet as the British critic Jonathan Dollimore wrote:

It’s one of the delusions of identity politics to think that our desire comfortably coexists with our identity, a belief which has more to do with consumerism than desire. I’ve come to feel that sexuality might at different times express different aspects of one’s self, a situation further complicated by the fact that the self changes.

My memory of the Ball is that it both reinforced and subverted identities, that it allowed people to mix across lines of gender, sexuality and age in ways that should not be reduced to the politically acceptable terminology that confuses sexual desire, gender expression and physical experience.

As I grow older I am happy to be honoured, and I loved the women who early on in the film talk about the need for an early start and a sit down dinner. But for one evening at least the Ball allowed people to mingle across lines of class, gender and, above all, generations.

The film ends with a very uplifting moment for one of the women, which I will conscientiously not reveal. But somewhere it lost the exuberance and magic that Tristan conjured up that evening in the Melbourne Town Hall. The best news of the night is that the Ball will happen again later this year.

Dennis Altman, Professorial Fellow in Human Security, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.