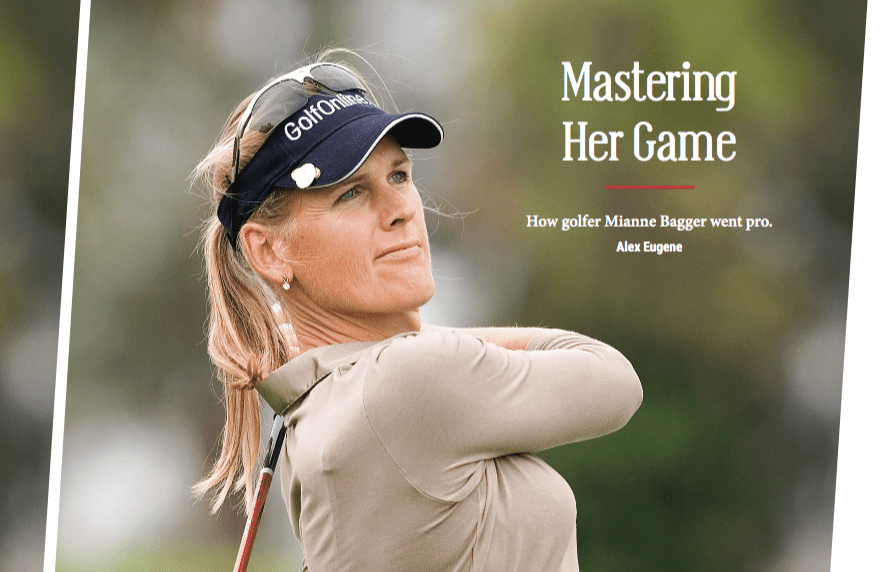

Mianne Bagger grew up with golf; it was a family tradition. Although children often lack the patience to learn the game, Bagger says she enjoyed it even as a child.

First in Denmark, then in Australia, “almost every summer weekend was a golf club trip. Our parents played while we kids ran around and did whatever we wanted. We had lessons, hit on the range, and ate ice cream. It was a fun experience,” she remembers.

Later in life, when Bagger found herself at the top of the Australian amateur golf rankings, it would have been perfectly logical for her to go on to the next level and turn pro. That choice was more complex for her than for most people, however. Bagger stayed in the amateur game as long as she did because she thought she could never go further.

The reason: Bagger identifies as an XY woman. Born initially male, she transitioned to female, undergoing hormone therapy and surgery.

“All the organisations had rules about being born female. I thought, let’s see if they’ll consider changing them,” she says.

Bagger started with a mini tour in Sweden. She contacted the organisers and sent them information about studies she’d found detailing research about XY women. The widespread—and incorrect—belief at the time (and even today) was that an XY woman might have an unfair advantage because of the testosterone in her body. But in reality, an XY woman can no longer produce the hormone naturally after surgery.

Within two weeks, the Swedish golfing organisation wrote back to say that a decision had been made: Bagger could join the tour. The event set her international career in motion. In time, other organisations amended their policies, allowing her to participate, and she played professionally in Australia and throughout Europe. The rest is history.

“Misinformation is still rife regarding transitioned women.”

However, despite the enormous amount of media attention Bagger received during her 11-year career as a professional golfer, misinformation is still rife regarding transitioned women. Bagger quickly explains that the language used to discuss transitioned people is not specific enough. “It’s essential to differentiate between gender and sex. We all use ‘gender’ because it’s a nice, polite term, and it’s not the word ‘sex,’ ” she says.

Bagger is often referred to as a transgender woman—but stresses that she does not identify with this term.

“An XY woman is born with XY chromosomes, someone born male but has fully transitioned. I’ve had surgical, anatomical changes. The impact is permanent and irreversible. Transgender women can come off hormone blockers at any time, and everything is restored,” she explains.

Bagger isn’t concerned about clarifying this confusing language just for the sake of argument. Correcting misunderstandings and reaching a consensus will determine who should and shouldn’t participate in professional sports.

“A transgender woman [who has not had gender reassignment surgery] has a male endocrine system capable of producing testosterone. That means if they were to come off hormone-blocking drugs, testosterone would start ringing back up again. Then, doping in sports becomes the issue,” Bagger explains.

Doping scandals have rocked sports worldwide, and current drug testing is random. So—as Bagger rightly points out—how is the hormonal state of a transgender woman to be monitored? Bagger doesn’t claim to have the answer yet.

“I think society has to allow sports to make mistakes. It’s a work in progress. The best thing is that everyone contributes collaboratively. Let’s move toward a workable solution,” she says.