172

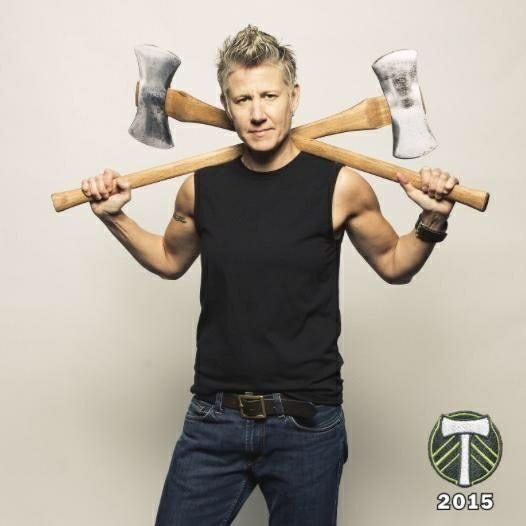

In 2015, I had the honour of being on a Timbers FC billboard.

Choosing who would be on one of these iconic billboards was nerve-racking. Hundreds of Oregonians competed for online votes for an entire week, pushing for their photo to be chosen. I somehow ended up winning with the most votes.

As a butch lesbian who always felt like an outsider, I was both shocked and humbled. There I was, muscles flexed as I posed with two axes over my shoulders and a daunting bravado, asking onlookers, “You wanna a piece of me?”

What a transformation from a closeted little girl, scared to admit she was gay, to an out, big butch lesbian on a twenty-foot billboard. It was a very proud and monumental moment in my life. It was also a gateway to meeting a young little lesbian named Snapper.

Shortly after the billboard went up, a client asked if I’d meet with her friend, whose daughter, Snapper, was a lesbian. The afternoon I met Snapper, she was dressed in Bermuda shorts and a navy blue, crisp short-sleeve shirt buttoned up to her chin.

Her short, combed-over haircut, rosy, plump cheeks, and dimples landed her in the ‘cute overload’ category. She was shy and barely audible when she spoke, but when asked by her mom if she was a lesbian, her answer was a no-nonsense, hands-down (albeit quiet), ‘yes.’ I sat there in awe, my mind blown away at the depth of her self-awareness and maturity. What a courageous seven-year-old girl. I couldn’t imagine grasping my sexual orientation at that age, let alone having the courage to speak openly about it.

I was lost momentarily as to why Snapper wanted to meet, knowing nothing about me except that I was on a billboard. Her family loved and accepted her wherever she fell on the LGBTQ+ spectrum. So why the desire to meet? Then the lightbulb went off, and I realized, “Duh, I looked like Snapper.” She was a baby butch lesbian, a sort of ‘mini-me.’ And even though her immediate family loved and supported her, homophobia still existed everywhere. Snapper most likely needed to see someone who was like her, an older butch lesbian who could assure her that she was normal and beautiful.

I grew up as a closeted lesbian in the late 1970s. For the longest time, I thought I was a tomboy, as I always gravitated towards stereotypical boy activities, like playing with toy trucks and digging for hours in the mud. My daily clothing consisted of jeans, usually with holes in the knees, and t-shirts covered with dirt. “She’ll grow out of it,” I heard frequently.

Ultimately, what I began to understand was that it wasn’t my outward tomboy appearance or behaviour that was concerning to the outside world; it was my sexual orientation. I was a lesbian, born in a period when few people were out of the closet; definitely, no one was out in my world. Homophobia was part of the culture at the time. Jokes and snide commentary about the ‘homosexuals and gays’ were part of the daily vocabulary in school hallways, locker rooms, television and every so often, around the dinner table.

Having no one to turn to, and indeed no out-of-the-closet gay role models, life was almost unbearable. Each morning, I put on my cloak of heterosexuality and pretended to be straight, acting like I was just like everyone else—” normal.” Then, every night, as my façade fell to the floor, I hid under my blankets and cried myself to sleep, thinking for sure I was abnormal. I lay in the dark, desperately longing for love, wondering why someone like me— so caring and kind— was born into a world intent on denying that love. I yearned for someone – anyone – that would see the real me.

For years, I acted and often successfully convinced myself I could be straight. I started drinking young, which helped dull my mind and senses into believing that this dysfunctional strategy would work. But ultimately, there was no way around it; I had always been one big lesbian, a tomboy and a lesbian. However, it wasn’t until I was 26 years old that I found the courage to come out. My courage came from meeting my first love in college. Even in the mid-1990s, homophobia was still widespread and without the support of another lesbian, I wasn’t sure I would’ve come out then.

However, in the early 2000s, more and more people started venturing out of the closet. Society was still not readily accepting of us, but change was happening. Gay Pride parades, protests against anti-LGBTQ legislation, and marches on Washington became more prevalent. Ellen DeGeneres had her famous “I’m Gay!” moment, which, for lesbians like me, was a joyful occasion. A lesbian on national TV announcing she was gay! She was me, and I, her. Perhaps she was a bit more entertaining and funny, but she was an out lesbian, like me! It meant the world to me and many others who, for years, thought we were abnormal.

The first time I saw Snapper, she awaited my arrival on the balcony of her home in the Northwest hills of Portland. When I pulled up, I heard, “She’s here, Mom! She’s here!” Laughing and unsure what I was walking into, I parked and headed to the front door. “Welcome!” Jaimee, Snapper’s mother, said as she motioned me inside. Turning to Snapper, I put out my hand and said, “It is a pleasure to meet you. I love your outfit! Very dapper!” This brought on a huge smile she was trying to contain, followed by a quiet “Thank you.” Jaimee lovingly laughed and said, “She changed her outfit five times before you arrived and, at one point, had on a tux.” It took everything I had to conceal my reaction. My heart was nearly bursting with adoration and love.

In our relaxed back-and-forth conversation on a variety of everyday topics, it finally came to light that Snapper was sometimes bullied and misgendered in school. In her world, she looked and possibly acted differently than most girls her age. And being an out lesbian, I’m sure she was an easy target. This sort of ridicule left her feeling isolated and alone. It’s too much for a ten-year-old kid. It’s often too much for grown adults. This, I understood.

“You know,” I started, “Being a butch lesbian and having a very masculine appearance, I’ve been teased a lot in life. And I still get misgendered all the time.” As I said this, I caught a sliver of a smile and quickly disappeared. “Well, what do you do when they call you a boy?” she asked. “It depends, I guess. Usually, people are just ignorant and oblivious, so I correct them and tell them I’m female. Most people are slightly embarrassed and apologize quickly,” I said. Then added, “But you know, some people are just jerks. Ignore them if you can. They’re just insecure and need to make others feel bad.”

The conversation continued, and she invited me to see her room. I forgot what a big deal it was to show other people the cool shit in your room, especially to adults. Unfortunately, I have no memory of what she showed me. It seemed almost surreal that I was in this stranger’s house, listening to a young butch excitedly rattle on about what she was into. I had moments of holding back tears as the entire situation overwhelmed me. I knew I wanted to be a role model and help other LGBTQ people, but I always thought it would be more in line with visibility and the creation of community events; it never crossed my mind that I could be an in-person, giant mirror for a young butch lesbian.

Now a young teenager, Snapper’s excelling in school and life. She’s even had her first girlfriend, something I couldn’t fathom in my day! Jaimee recently shared my importance in Snapper’s life: “In a time Snapper could have regressed to shadows, you pulled her to the front. I will never forget that—or be able to repay you that debt,” she said. Ironically, I feel I owe her a debt. Having Snapper enter my life brought many things full circle. It allowed me the opportunity to help someone else trying to navigate a sometimes frightening, homophobic and transphobic world. I could be a visible, living example of hope and share something precious I never heard when I was young: You are 100% beautiful and typical.

“Shaley Howard is the author of Excuse Me, Sir! Memoir of a Butch”